Outlines of Louis F. Post's Lectures

on The Single Tax ~ Absolute Free Trade ~ The Labor Question ~ Progress and Poverty ~ The Land Question ~ The Elements of Political Economy ~ Socialism ~ Hard Times

with Illustrative Notes & Charts

and FAQ

copyright 1894

Prefatory Note

I. The Single Tax Defined

II. The Single Tax as a Fiscal Reform

1. Direct and Indirect Taxation

2. The Two Kinds of Direct Taxation

(1) In proportion to ability to pay; and (2) in proportion to benefits received.

3. The Single Tax Falls in Proportion to Benefits

4. Conformity to General Principles of Taxation

(a) Interference with Production

(b) Cheapness of Collection

(c) Certainty

(d) Equality

III. The Single Tax as a Social Reform

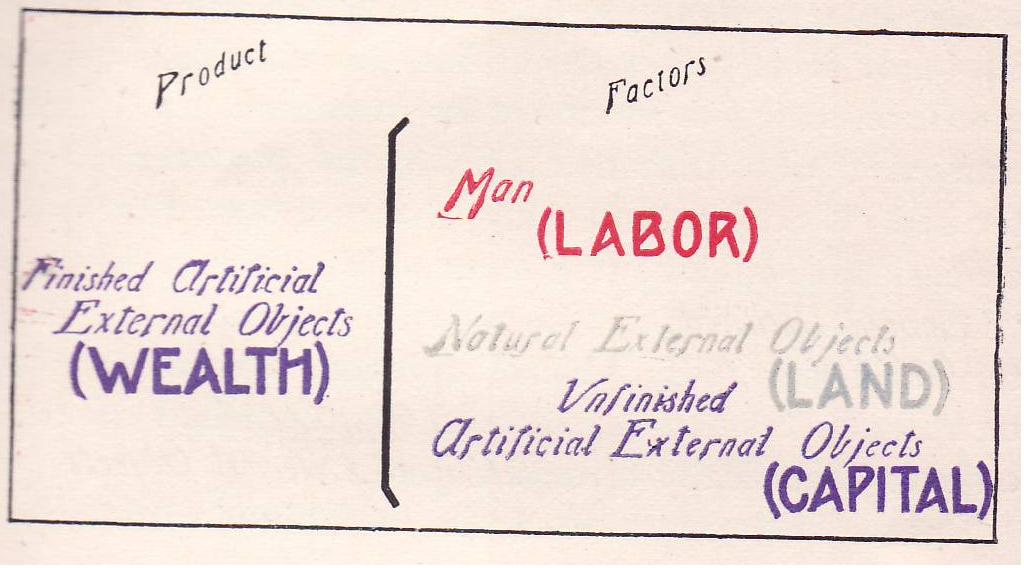

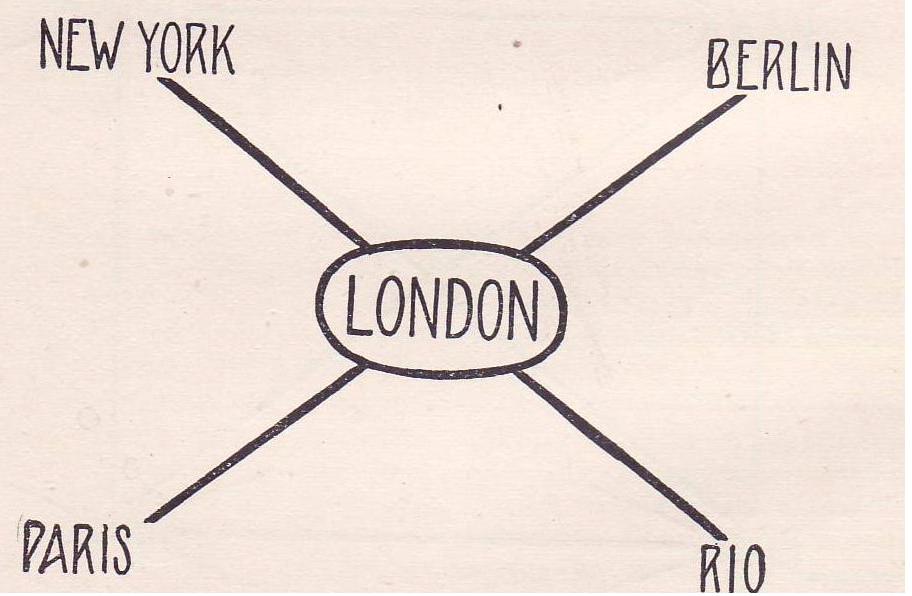

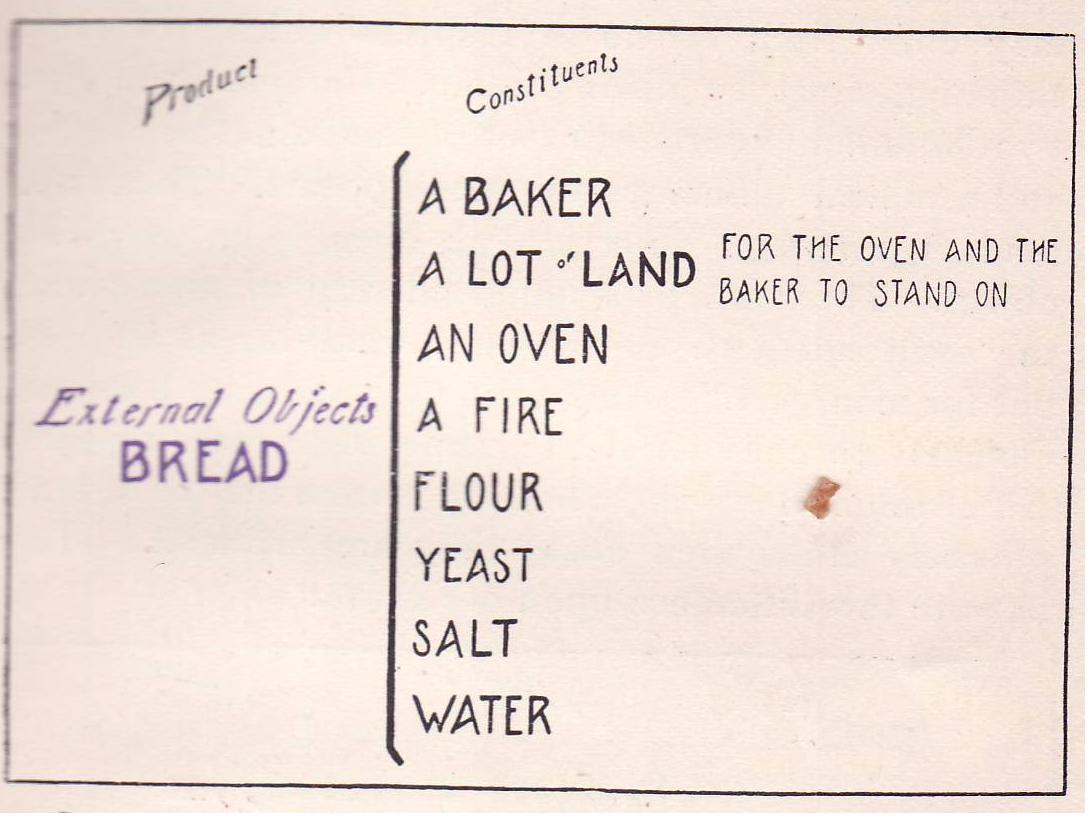

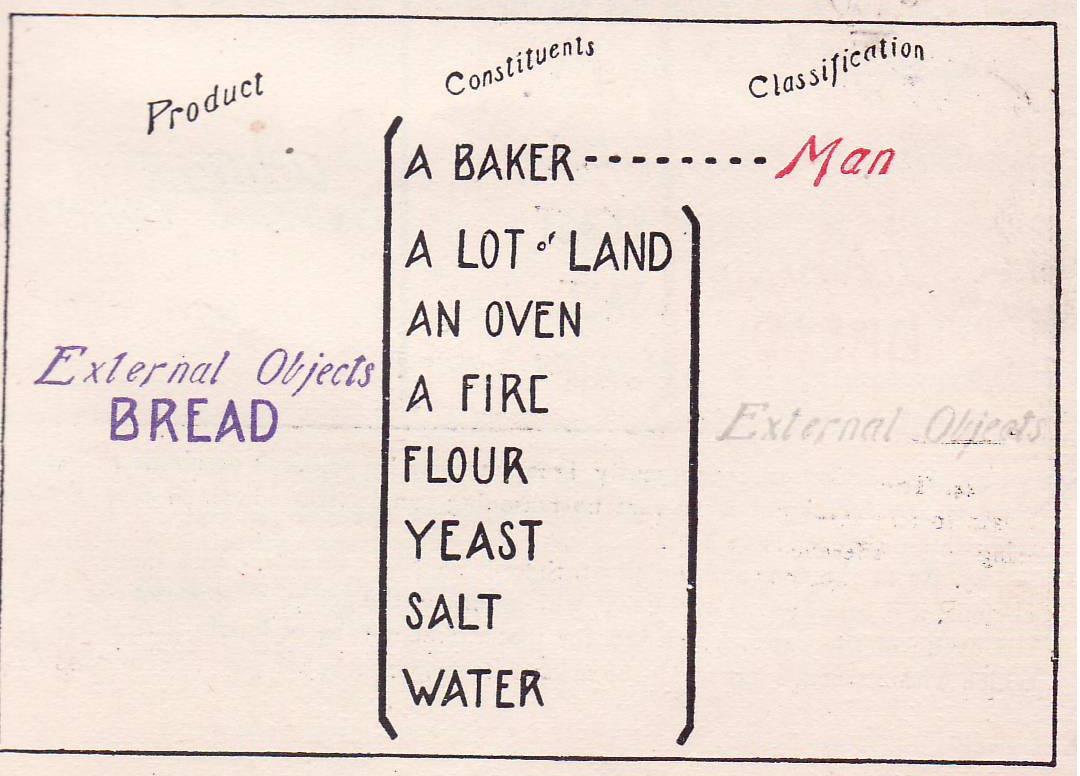

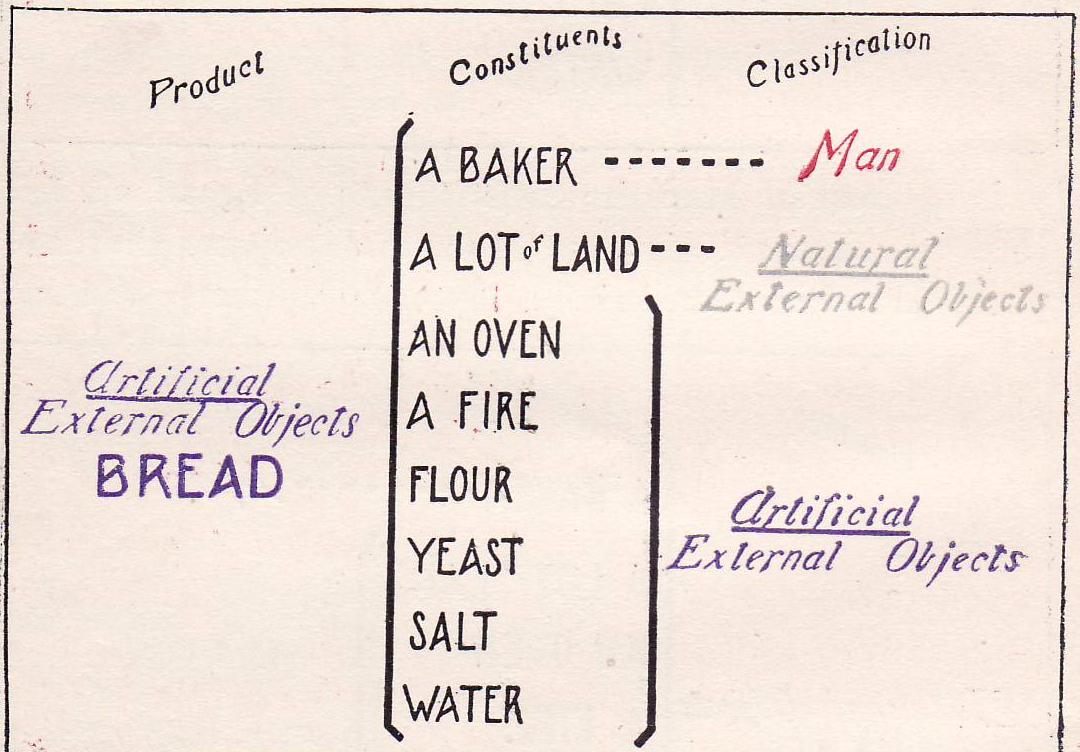

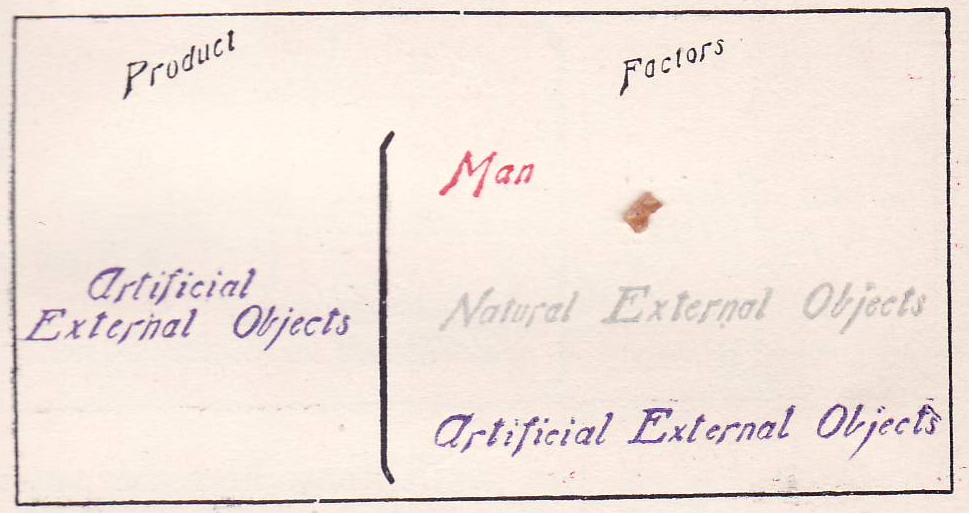

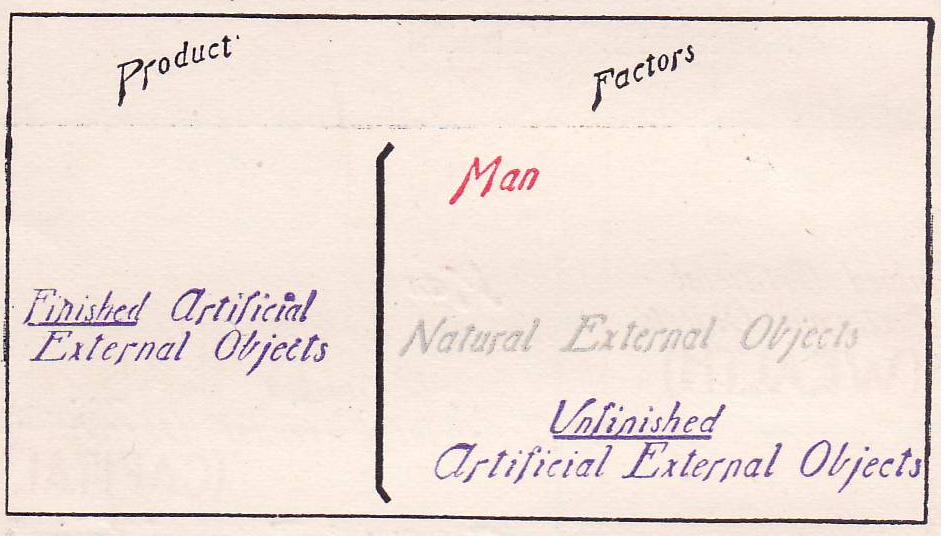

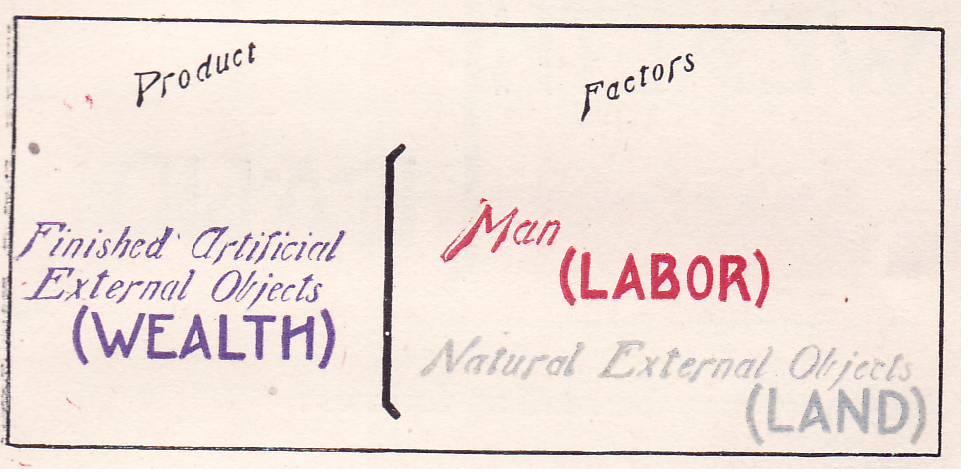

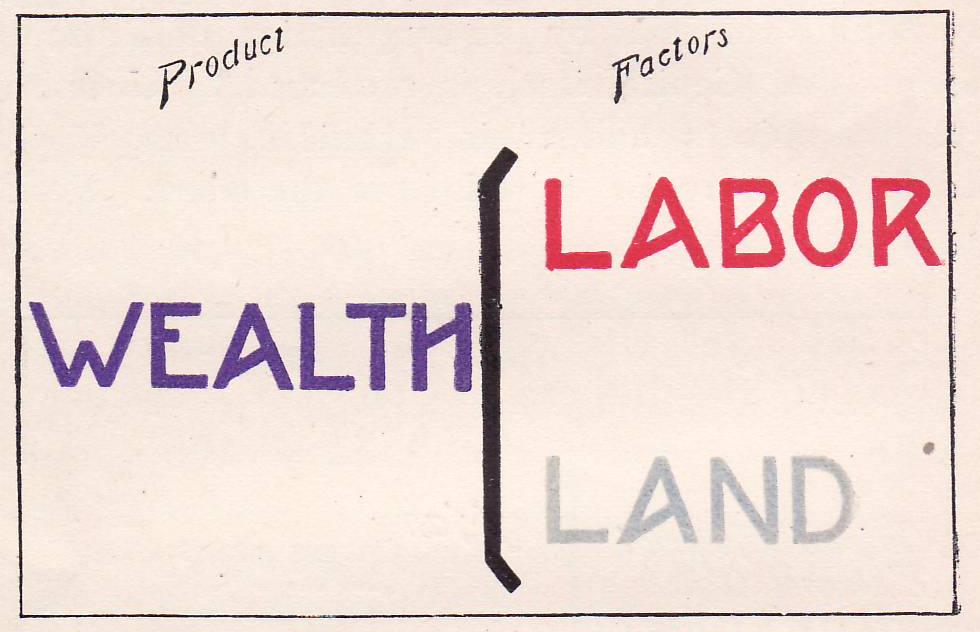

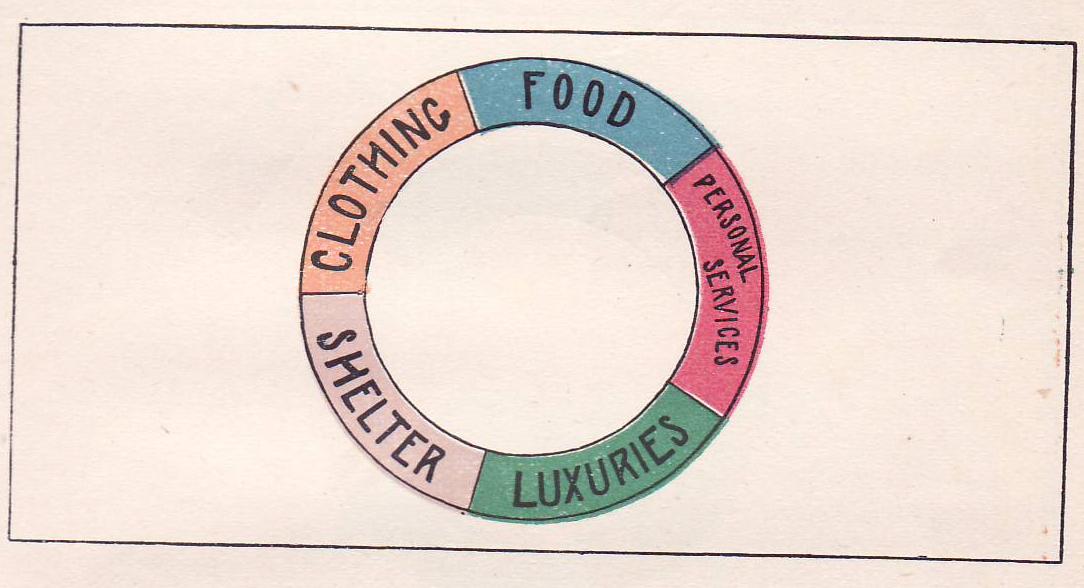

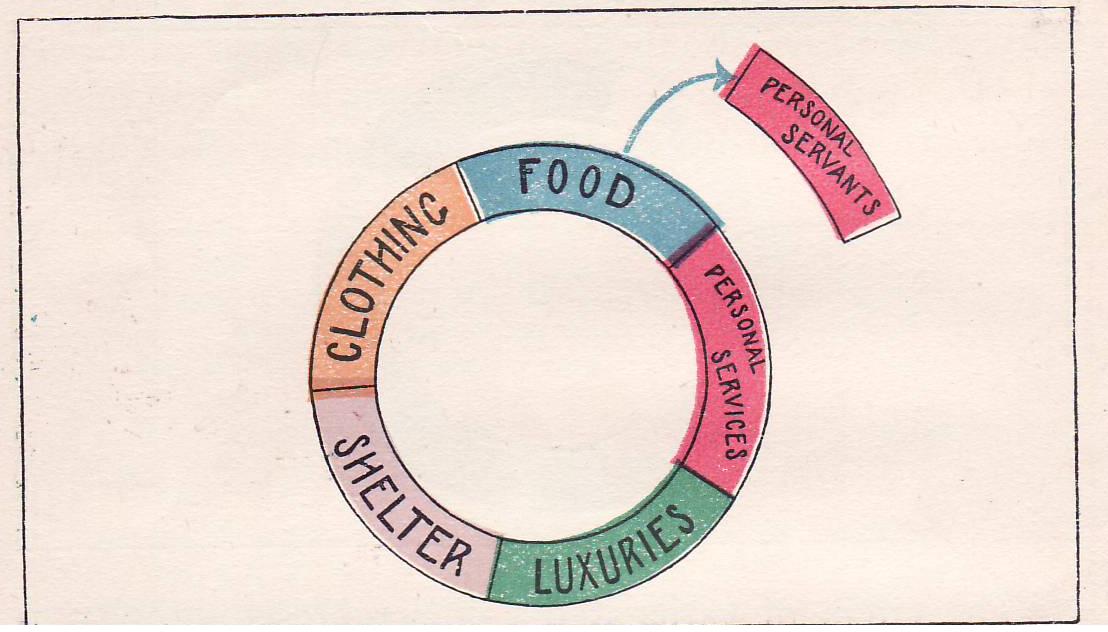

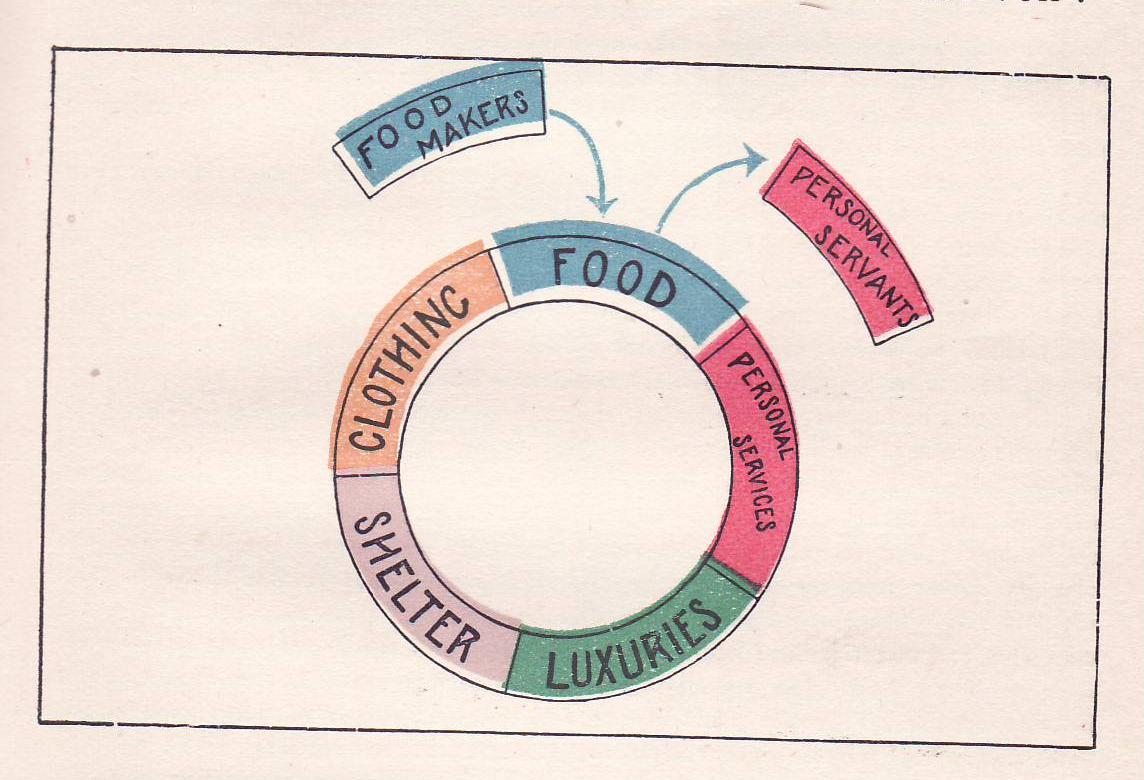

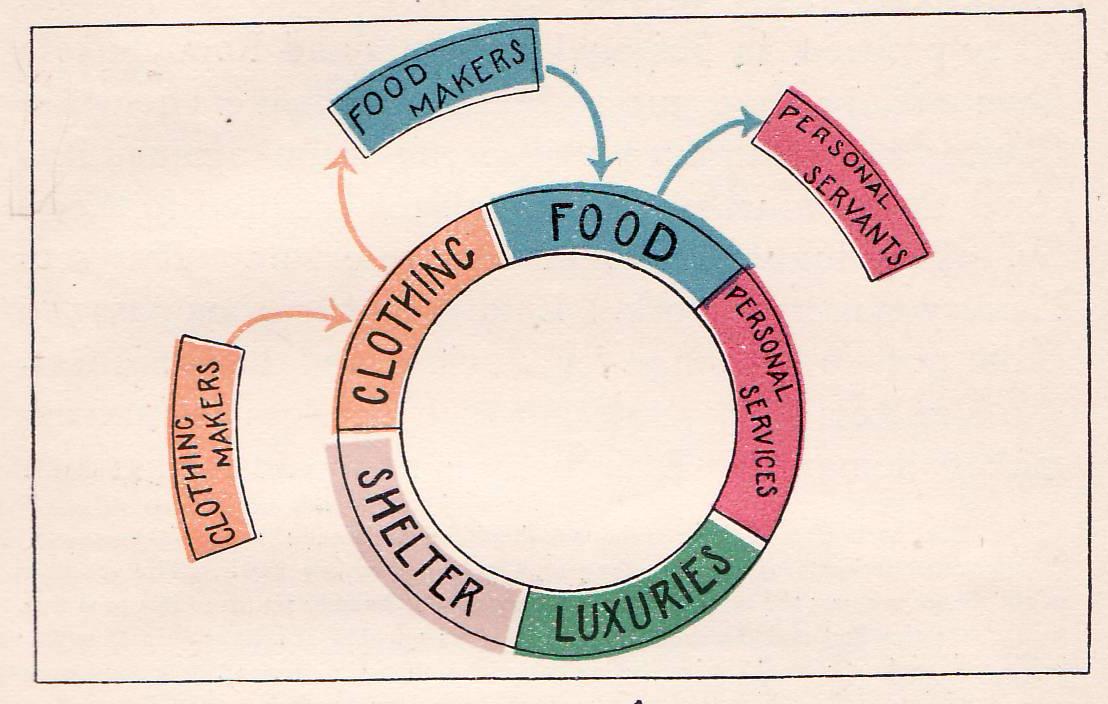

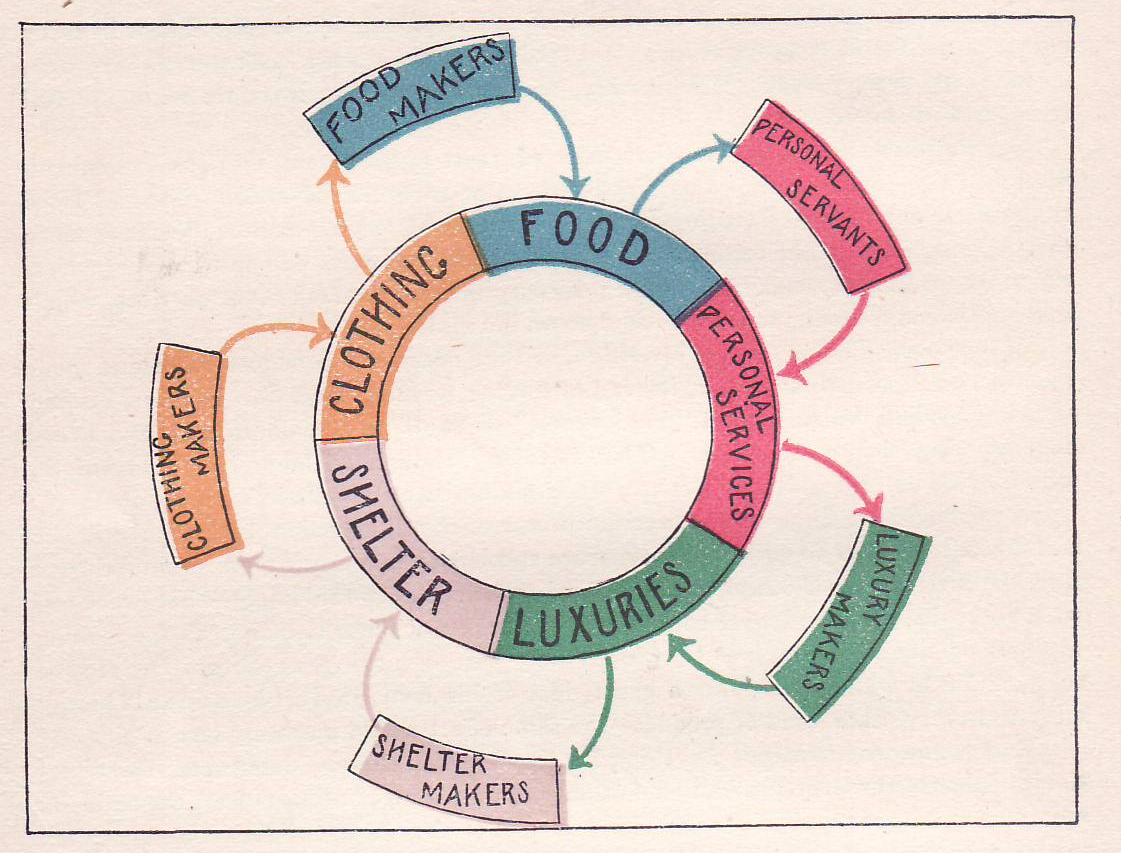

1. The Source of Wealth (Charts)

2. The Production of Wealth

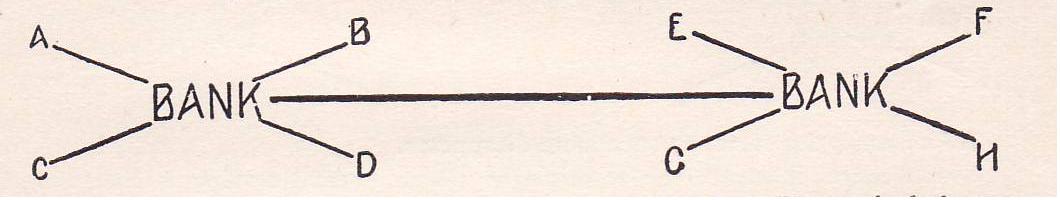

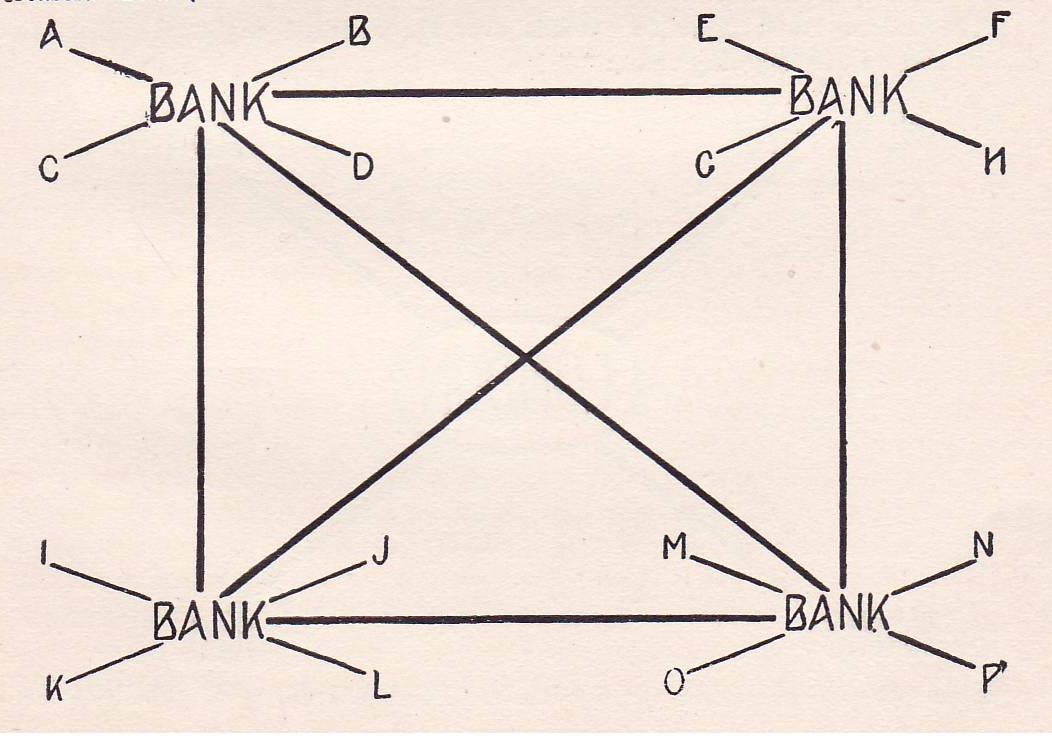

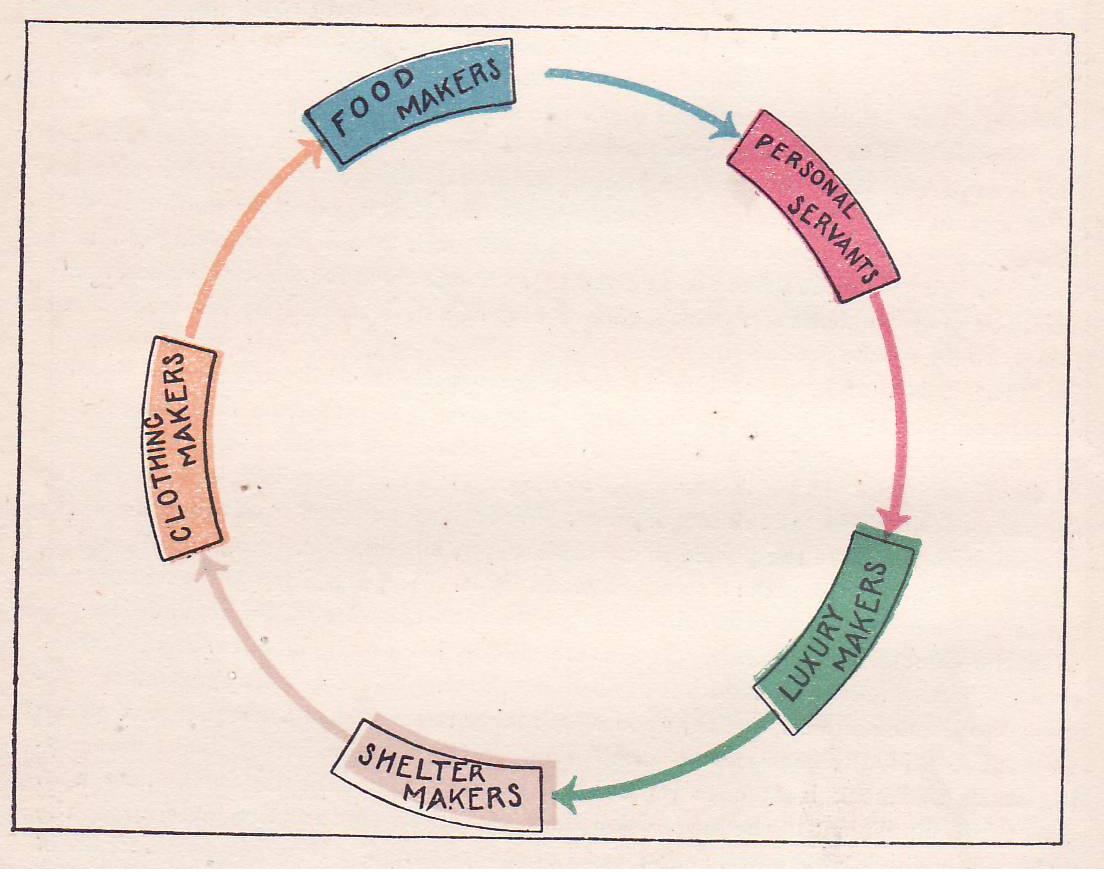

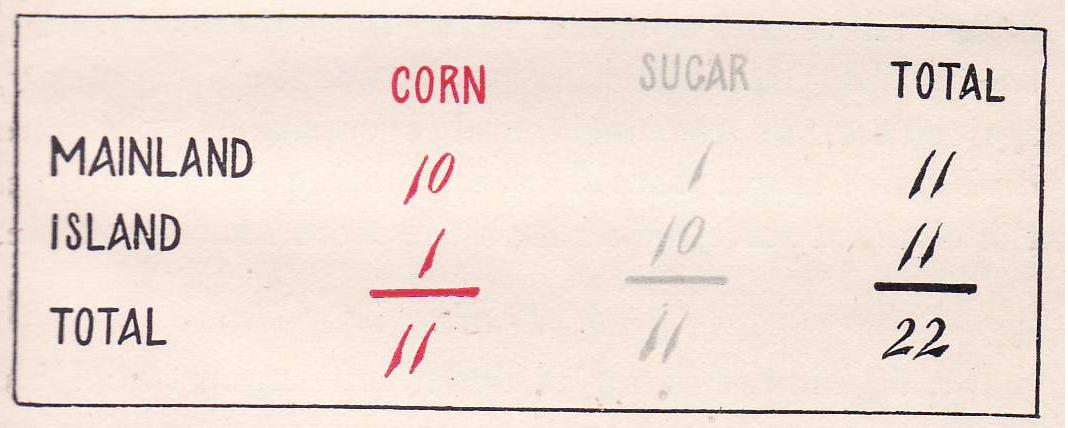

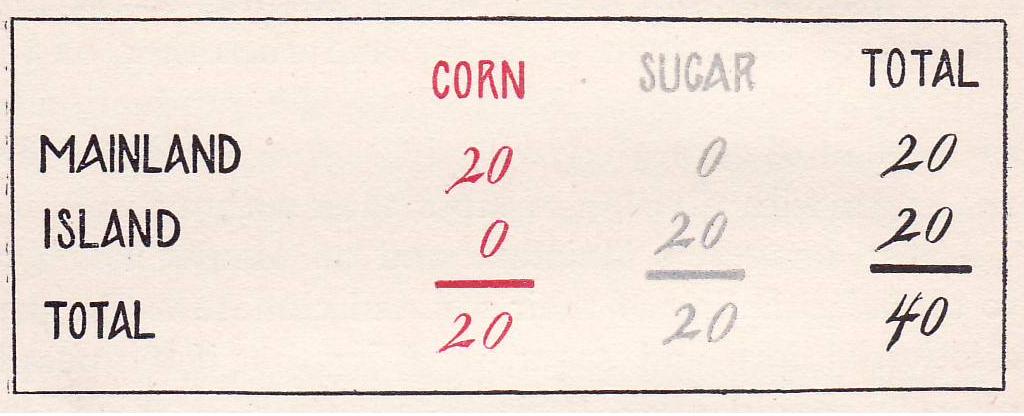

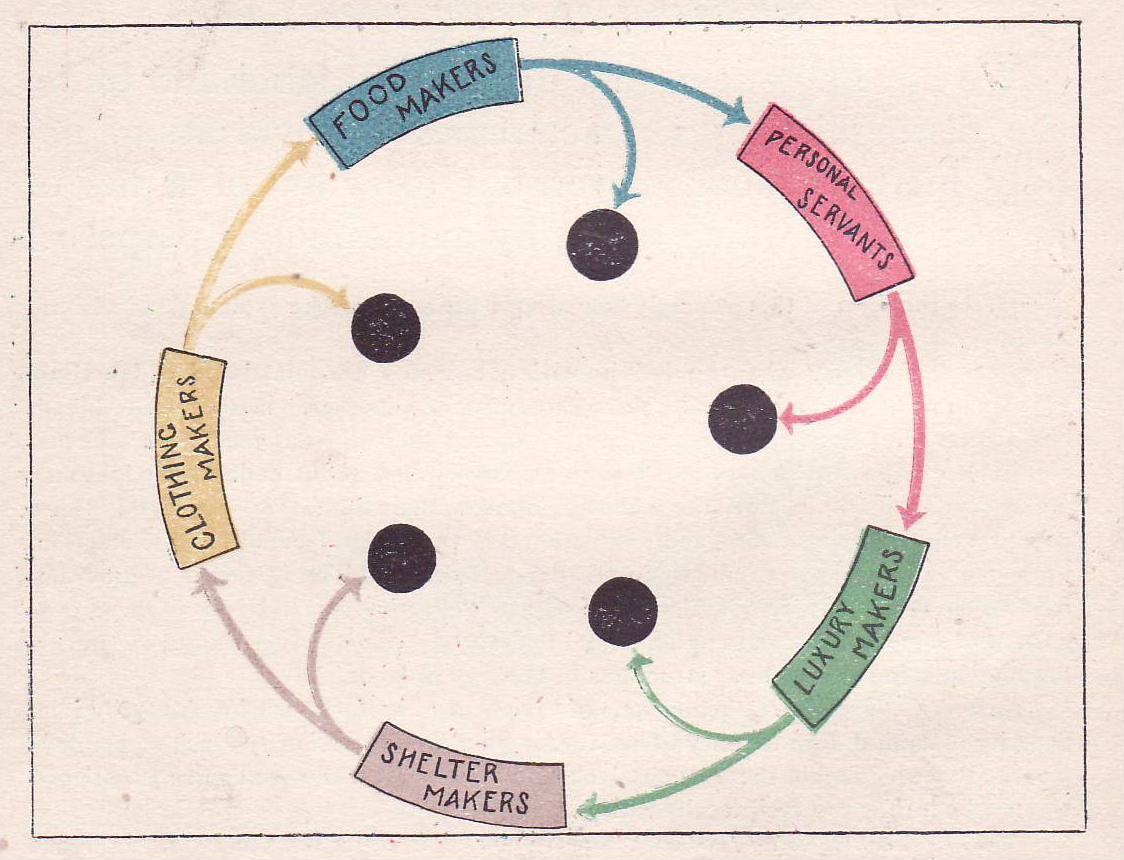

(a) Division of Labor (Charts)

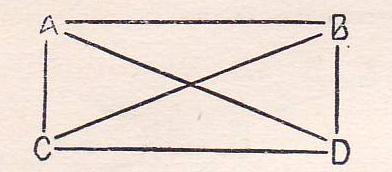

(b) Trade (Charts)

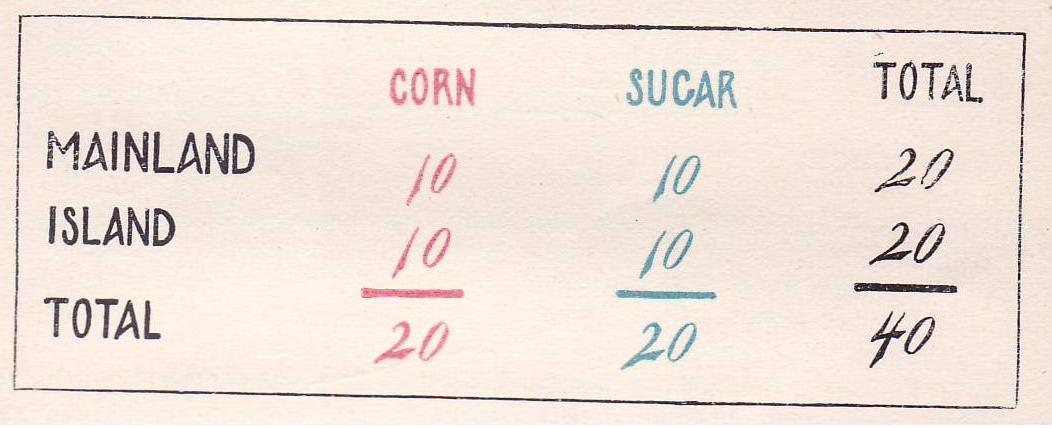

(c) The Law of Division of Labor and Trade (Charts)

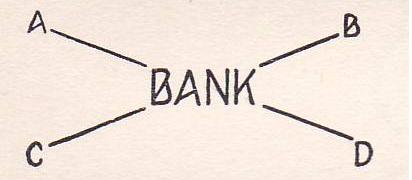

Note 72. Mechanism of Trade (Charts)

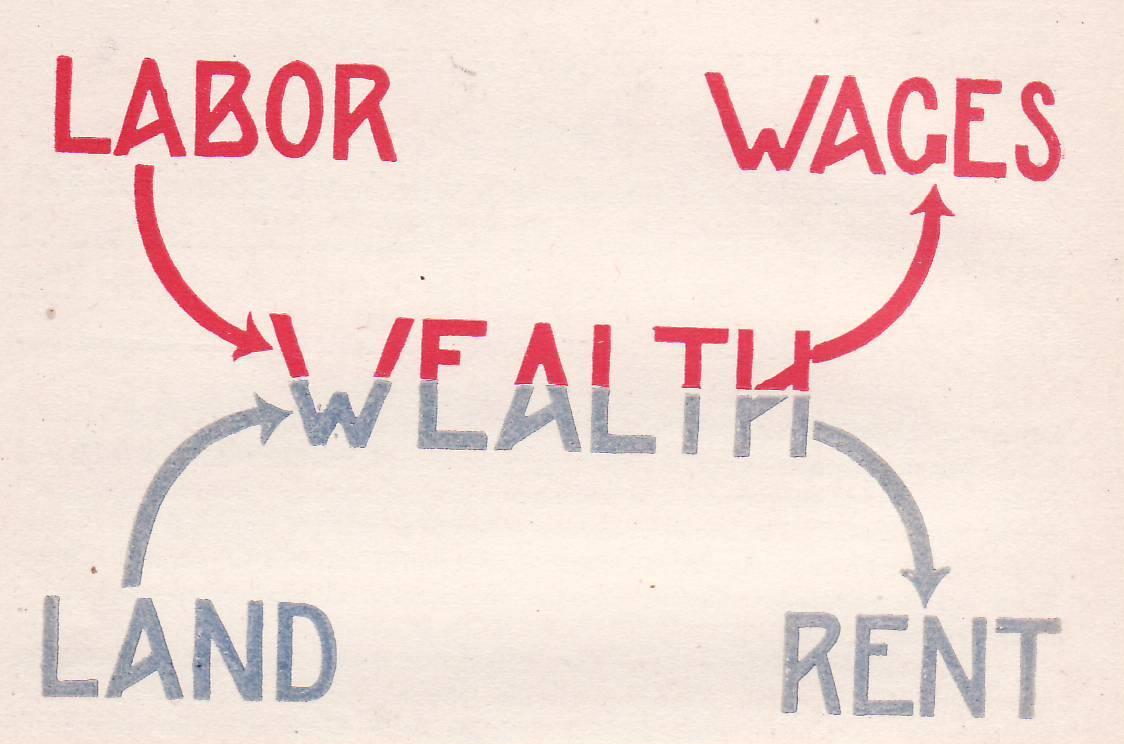

(d) Dependence of Labor Upon Land (Chart)

3. The Distribution of Wealth

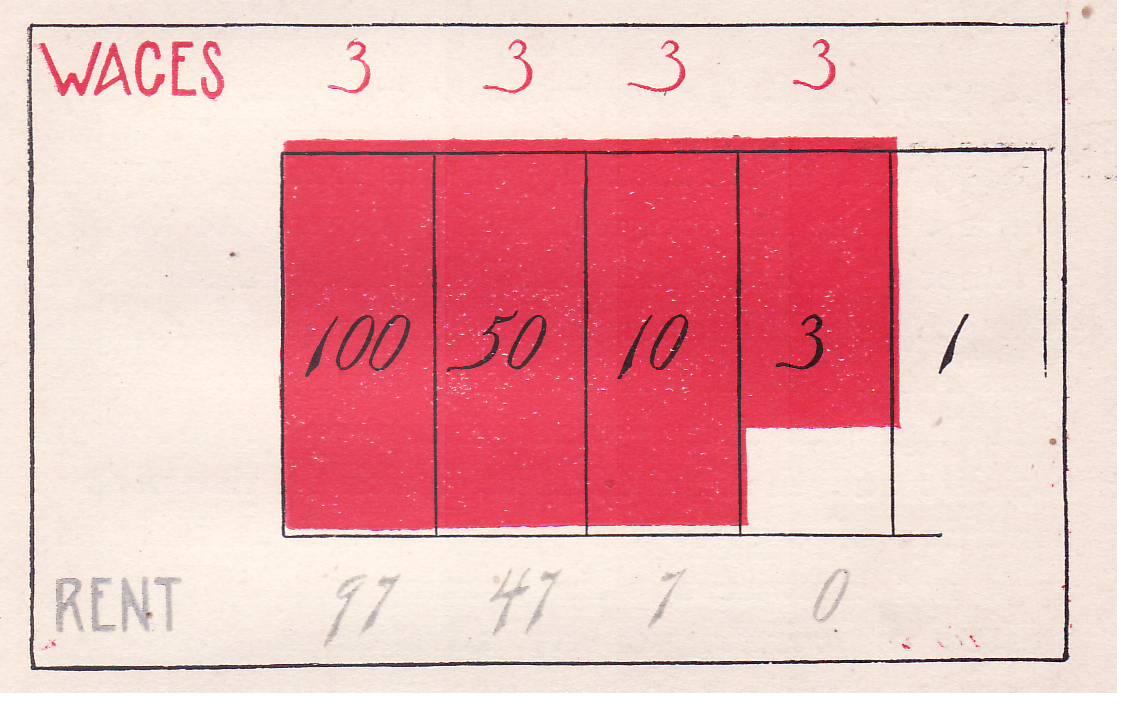

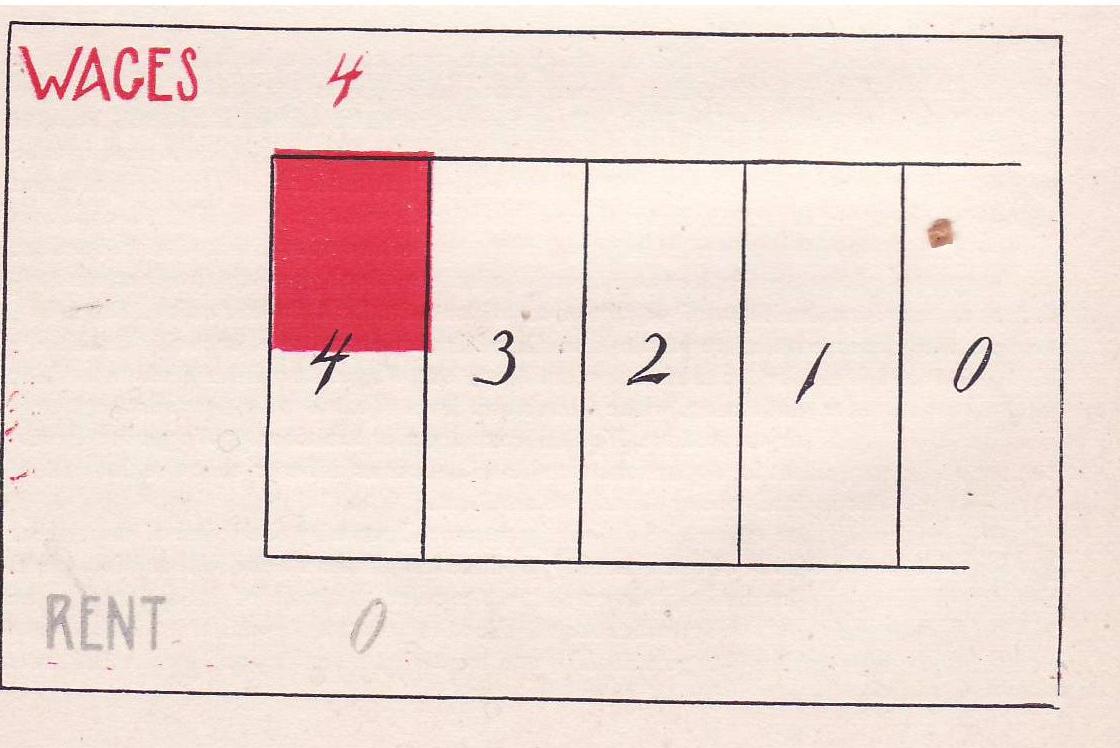

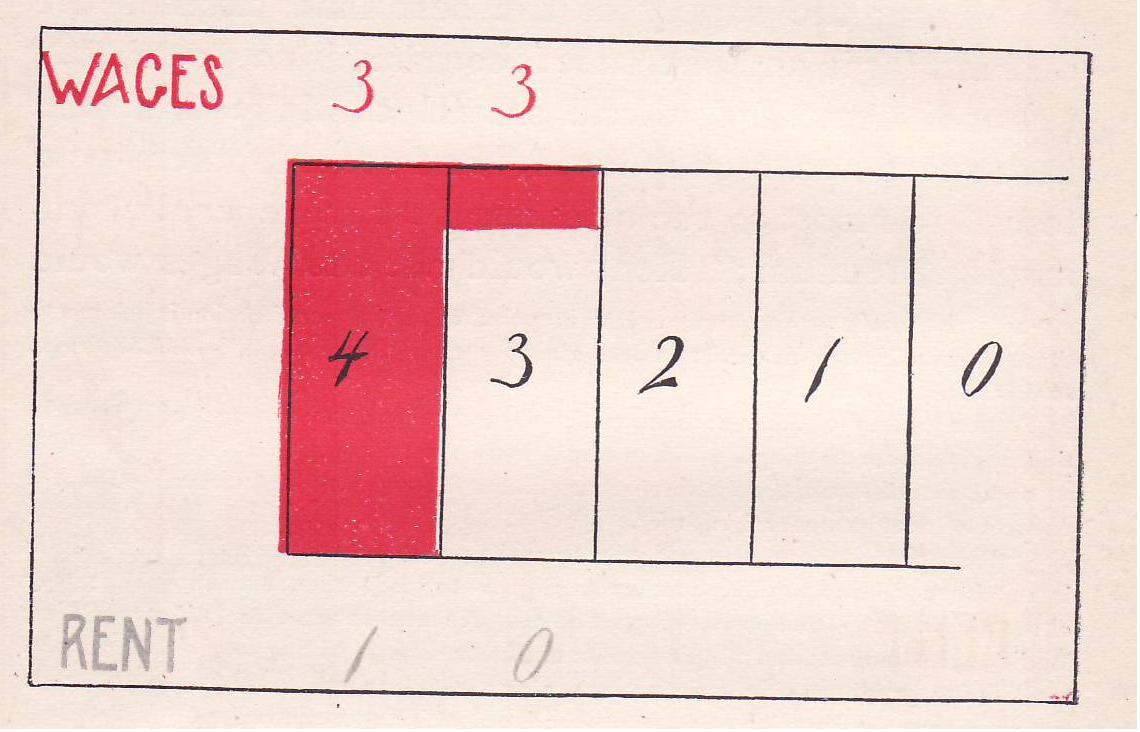

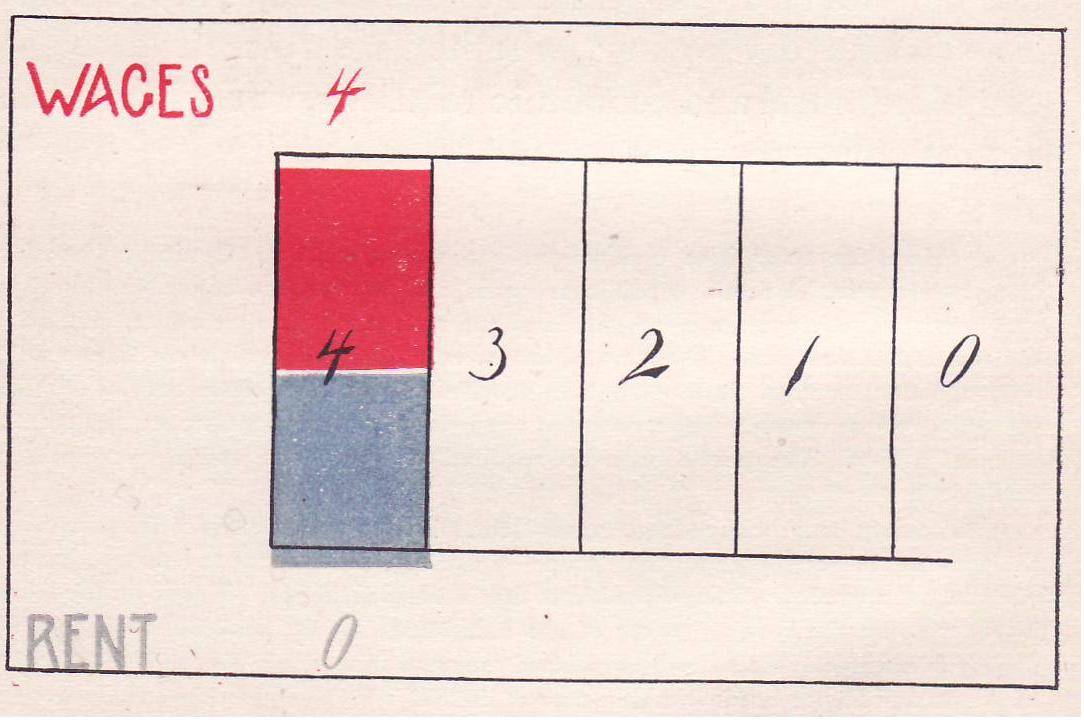

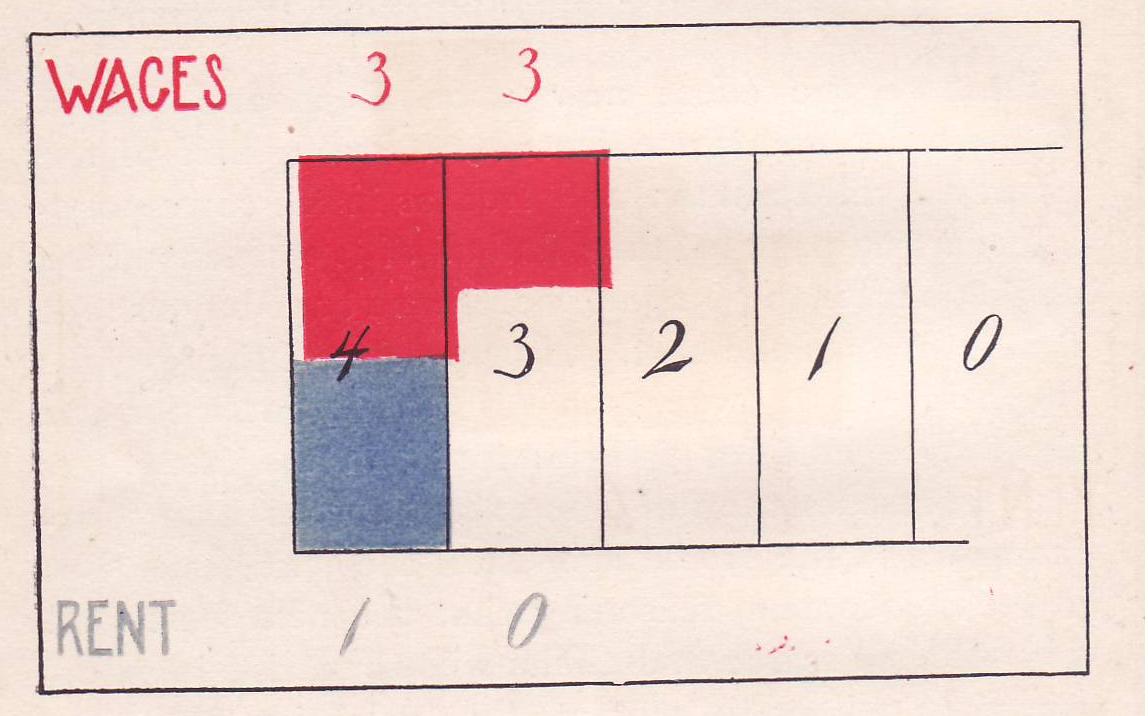

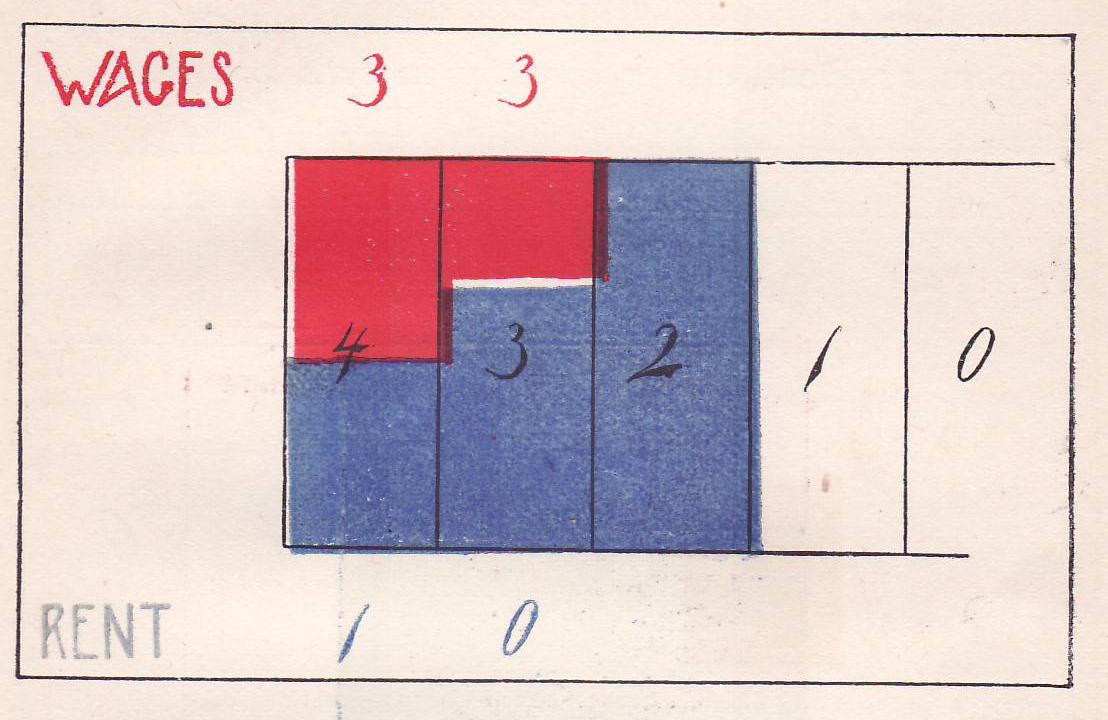

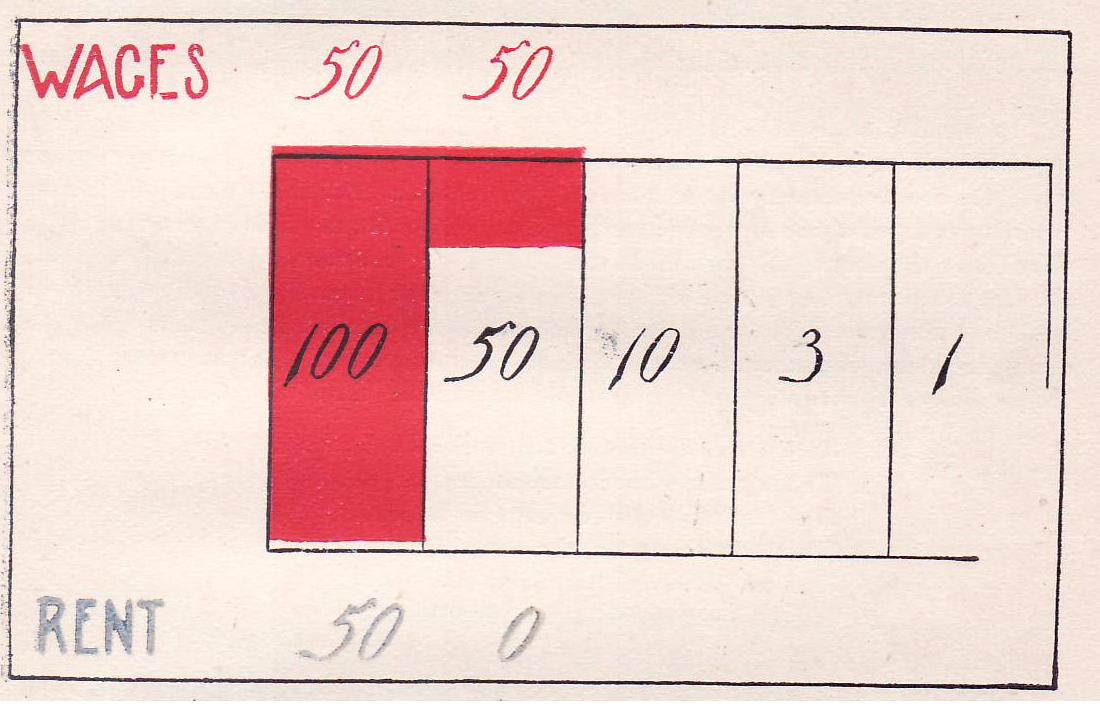

(a) Explanation of Wages and Rent

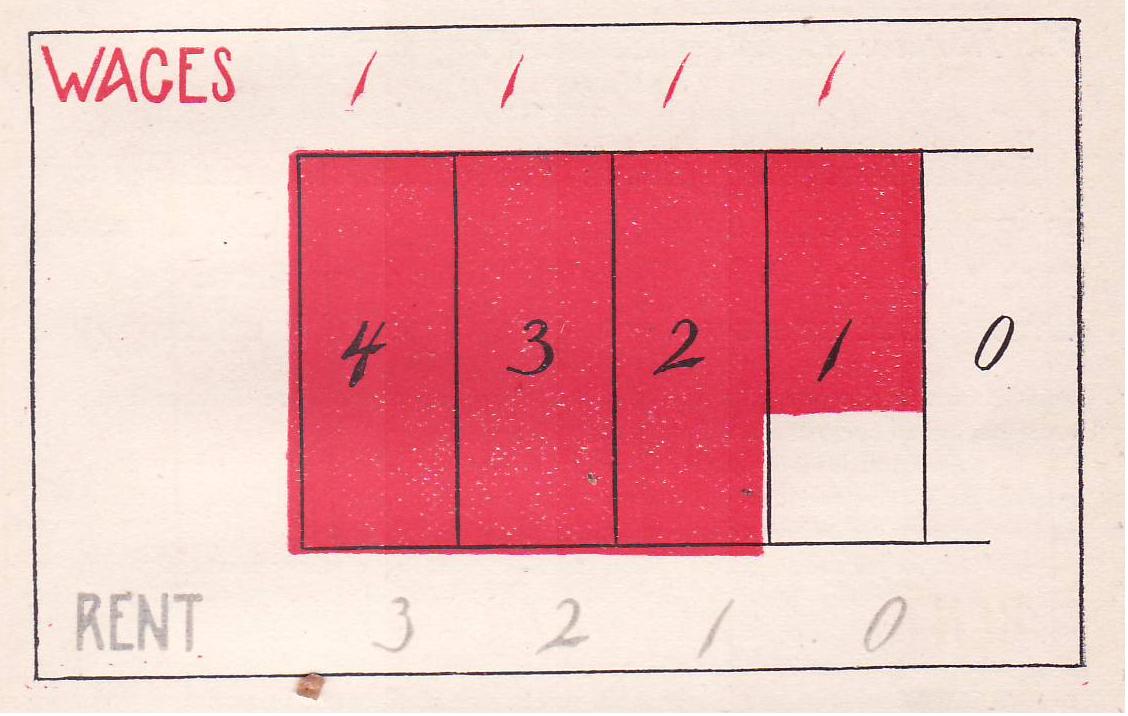

(b) Normal Effect of Social Progress upon Wages and Rent

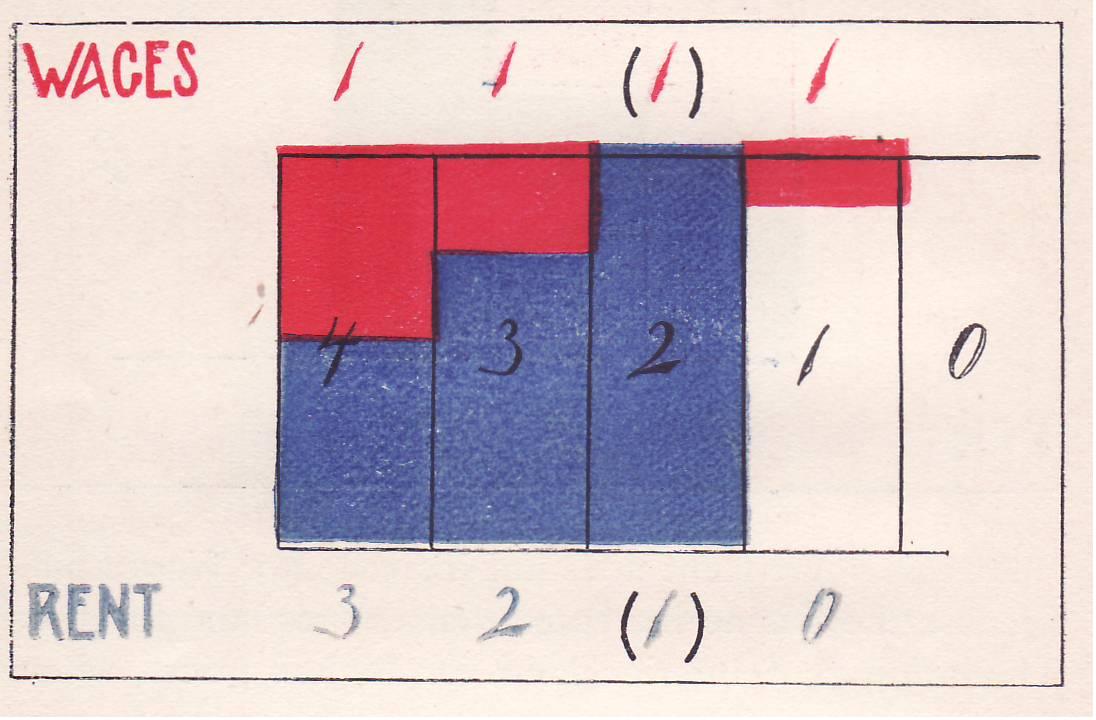

(c) Significance of the Upward Tendency of Rent

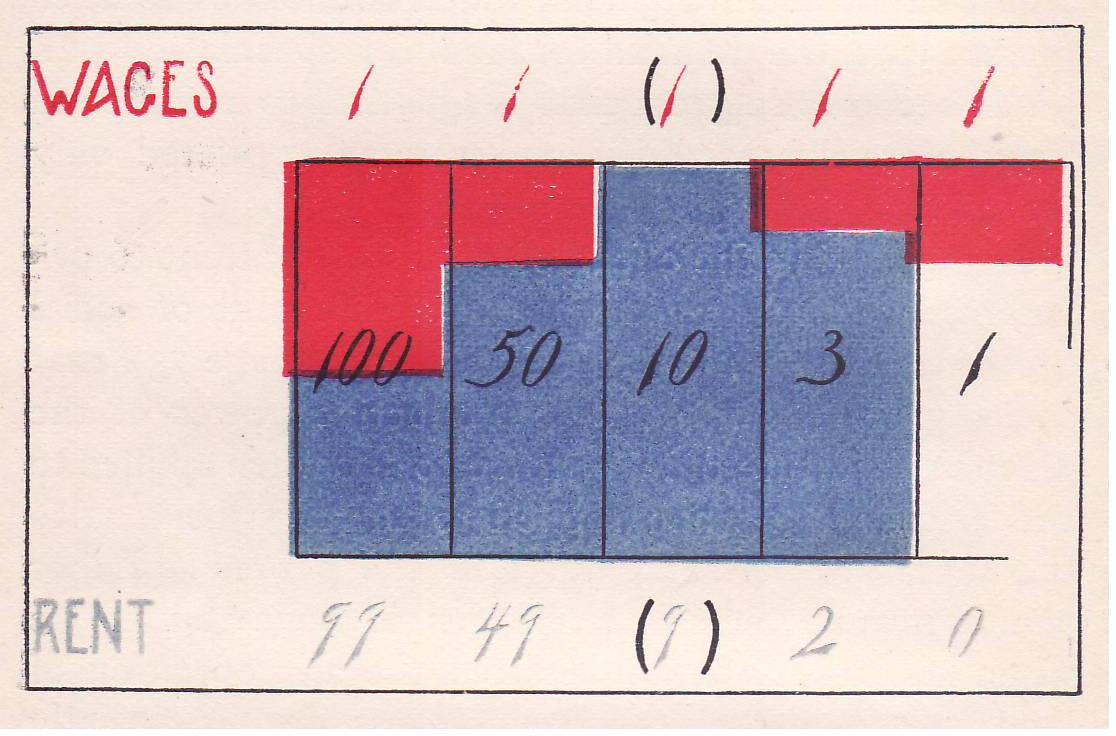

(d) Effect of Confiscating Rent to Private Use

(e) Effect of Retaining Rent for Common Use

Conclusion

PREFATORY NOTE

These "Outlines," while giving neither the substance nor the arrangement of any of the lectures named in the title, contain the leading points of all. But to make the points consecutive they have been woven into one of the lectures — that on the Single Tax. This, however, is not arbitrary, for the philosophy of the single tax involves the elementary principles of absolute free trade, of the labor question, of poverty with progress, of the land question, and of political economy; and while exposing the fallacies of socialism it explains the problem of hard times.

The "Outlines" do not take the place of the lectures. They are published merely to prepare the mind of the reader in advance to more fully appreciate the lectures during delivery, and to assist afterward in recalling and deliberately considering and criticizing what is advanced from the platform. To this end the principal charts of all the lectures are reproduced.

The text in large type is a connected explanation. It may be read and fully understood without reference to the notes. But the notes elaborate and illustrate points which from the conciseness of their statement in the text may seem obscure to readers who are unaccustomed to economic thought.

I. THE SINGLE TAX DEFINED

The practical form in which Henry George puts the idea of appropriating economic rent to common use is "To abolish all taxation save that upon land values."1

1. "Progress and Poverty," book viii, ch. ii.

This is now generally known as "The Single Tax."2 Under its operation all classes of workers, whether manufacturers, merchants, bankers, professional men, clerks, mechanics, farmers, farm-hands, or other working classes, would, as such, be wholly exempt. It is only as men own land that they would be taxed, the tax of each being in proportion, not to the area, but to value of his land. And no one would be compelled to pay a higher tax than others if his land were improved or used while theirs was not, nor if his were better improved or better used than theirs.3 The value of its improvements would not be considered in estimating the value of a holding; site value alone would govern.4 If a site rose in the market the tax would proportionately increase; if that fell, the tax would proportionately diminish.

2. In "Progress and Poverty," book viii, ch. iv, Henry George speaks of "the effect of substituting for the manifold taxes now imposed, a single tax on the value of land; but the term did not become a distinctive name until 1888.

The first general movement along the lines of "Progress and Poverty" began New York City election of 1886, when Henry George polled 68,110 votes as an independent candidate for mayor, and was defeated by the Democratic candidate, Abram S. Hewitt, by a plurality of only 22,442, the Republican, Theodore Roosevelt, polling but 60,435. Following that election the United Labor Party was formed, the Syracuse Convention in August, 1887, by the exclusion of the Socialists, came to present the central idea of "Progress and Poverty" as distinguished from the Socialistic propaganda which until then was identified with it. Coincident with the organization of the United Labor Party the Anti-Poverty Society was formed; and the two bodies, one representing the political and the other the religious phase of the idea, worked together until President Cleveland's tariff message of 1887 appeared. In this message Mr. George saw the timid beginnings of that open struggle between protection and free trade to which he had for years looked forward as the political movement that must culminate in the abolition of all taxes save those upon land values, and he responded at once to the sentiments of the message. But many protectionists, who had followed him because they supposed he was a land nationalizer, now broke away from his leadership, and the United Labor Party and the Anti-Poverty Society were soon practically dissolved. Those who understood Mr. George's real position regarding the land question readily acquiesced in his views as to political policy, and a considerable movement resulted, which, however, for some time lacked an identifying name. This was the situation when Thomas G. Shearman, Esq., wrote for the Standard an article on taxation in which he illustrated and advocated the land value tax as a fiscal measure. The article had been submitted without a caption, and Mr. George, then the editor of the Standard, entitled it "The Single Tax." This title was at once adopted by the "George men," as they were often called, and has ever since served as the name of the movement it describes.

Though "the single tax" is the English form of "l'impot unique" the name of the French physiocratic doctrine of the eighteenth century, the names have no historical connection, and they stand for different ideas.

3. When it is remembered that some land in cities is worth millions of dollars an acre, that a small building lot in the business center of even a small village is worth more than a whole field of the best farming land in the neighborhood, that a few acres of coal or iron land are worth more than great groups of farms, that the right of way of a railroad company through a thickly settled district or between important points is worth more than its rolling stock, and that the value of workingmen's cottages in the suburbs is trifling in comparison with the value of city residence sites, the absurdity, if not the dishonesty, of the plea that the single tax would discriminate against farmers and small home owners and in favor of the rich is apparent. The bad faith of this plea is emphasized when we consider that under existing systems of taxation the farmer and the poor home owner are compelled to pay in taxes upon improvements, food, clothing, and other objects of consumption, much more than the full annual value of their bare land.

4. The difference between site value and improvement value is much more definite than it is often supposed to be. Even in what would seem at first to be most confusing cases, it is easily distinguished. If in any example we imagine the complete destruction of all the improvements, we may discover in the remaining value of the property — in the price it would after such destruction fetch in the real estate market — the value of the site as distinguished from the value of the improvements. This residuum of value would be the basis of computation for levying the single tax.

The distinction is frequently made in business life. Whenever in the course of ordinary business affairs it becomes necessary to estimate the value of a building lot, or to fix royalties for mining privileges, no difficulty is experienced, and substantial justice is done. And though the exigencies of business seldom require the site value of an improved farm to be distinguished from the value of its improvements, yet it could doubtless be done as easily and justly as with city or mining property. Unimproved land attached to any farm in question, or unimproved land in the neighborhood, if similar in fertility and location, would furnish a sufficiently accurate measure. If neither existed, the value of the contiguous highway would always be available.

It should not be forgotten that land for which the demand is so weak that its site value cannot be easily distinguished from the value of its improvements, is certain to be land of but little value, and almost certain to have no value at all.

The objection that the value of land cannot be distinguished from the value of its improvements is among the most frivolous of the objections that have been raised to the single tax by people with whom the wish that it may be impracticable is father to the thought that it really is so.

The single tax may be concisely described as a tax upon land alone, in the ratio of value, irrespective of improvements or use.

II. THE SINGLE TAX AS A FISCAL REFORM

1. DIRECT AND INDIRECT TAXATION

Taxes are either direct or indirect; or, as they have been aptly described, "straight" or "crooked." Indirect taxes are those that may be shifted by the first payer from himself to others; direct taxes are those that cannot be shifted.5

5. "Taxes are either direct or indirect. A direct tax is one which is demanded from the very persons who, it is intended or desired, should pay it. Indirect taxes are those which are demanded from one person in the expectation and intention that he shall indemnify himself at the expense of another." — John Stuart Mill's Prin. of Pol. Ec., book v, ch. iii, sec. I.

"Direct taxes are those which are levied on the very persons who it is intended or desired should pay them, and which they cannot put off upon others by raising the prices of the taxed article.. . . Indirect taxes on the other hand are those which are levied on persons who expect to get back the amount of the tax by raising the price of the taxed article." — Laughlin's Elements, par. 249.

Taxes are direct "when the payment is made by the person who is intended to bear the sacrifice." Indirect taxes are recovered from final purchasers. — Jevons's Primer, sec. 96.

"Indirect taxes are so called because they are not paid into the treasury by the person who really bears the burden. The payer adds the amount of the tax to the price of the commodity taxed, and thus the taxation is concealed under the increased price of some article of luxury or convenience." — Thompson's Pol. Ec., sec. 175.

The shifting of indirect taxes is accomplished by means of their tendency to increase the prices of commodities on which they fall. Their magnitude and incidence 6 are thereby disguised. It was for this reason that a great French economist of the last century denounced them as "a scheme for so plucking geese as to get the most feathers with the least squawking."7

6. Jevons defines the incidence of a tax as "the manner in which it falls upon different classes of the population." — Jevons's Primer, sec. 96.

Sometimes called "repercussion," and refers "to the real as opposed to the nominal payment of taxes." — Ely's Taxation, p. 64.7. Though his language was blunt, the sentiment does not essentially differ from that of "statesmen" of our day who meet all the moral and economic objections to indirect taxation with the one reply that the people would not consent to pay enough or the support of government if public revenues were collected from them directly. This means nothing but that the people are actually hoodwinked by indirect taxation into sustaining a government that they would not support if they knew it was maintained at their expense; and instead of being a reason for continuing indirect taxation, would, if true, be one of the strongest of reasons for abolishing it. It is consistent neither with the plainest principles of democracy nor the simplest conceptions of morality.

Indirect taxation costs the real tax-payers much more than the government receives, partly because the middlemen through whose hands taxed commodities pass are able to exact compound profits upon the tax,8 and partly on account of extraordinary expenses of original collection;9 it favors corruption in government by concealing from the people the fact that they contribute to the support of government; and it tends, by obstructing production, to crush legitimate industry and establish monopolies.10 The questions it raises are of vastly more concern than is indicated by the sum total of public expenditures.

8. A tax upon shoes, paid in the first instance by shoe manufacturers, enters into manufacturers' prices, and, together with the usual rate of profit upon that amount of investment, is recovered from wholesalers. The tax and the manufacturers' profit upon it then constitute part of the wholesale price and are collected from retailers. The retailers in turn collect the tax with all intermediate profits upon it, together with their usual rate of profit upon the whole, from final purchasers — the consumers of shoes. Thus what appears on the surface to be a tax upon shoe manufacturers proves upon examination to be an indirect tax upon shoe consumers, who pay in an accumulation of profits upon the tax considerably more than the government receives.

The effect would be the same if a tax upon their leather output were imposed upon tanners. Tanners would add to the price of leather the amount of the tax, plus their usual rate of profit upon a like investment, and collect the whole, together with the cost of hides, of transportation, of tanning and of selling, from shoe manufacturers, who would collect with their profit from retailers, who would collect with their profit from shoe consumers. The principle applies also when taxes are levied upon the stock or the sales of merchants, or the money or credits of bankers; merchants add the tax with the usual profit to the prices of their goods, and bankers add it to their interest and discounts.

For example; a tax of $100,000 upon the output of manufacturers or importers would, at 10 per cent as the manufacturing profit, cost wholesalers $110,000; at a profit of 10 per cent to wholesalers it would cost retailers $121,000, and at 20 percent profit to retailers it would finally impose a tax burden of $145,200 — being 45 per cent more than the government would get. Upon most commodities the number of profits exceeds three, so that indirect taxes may frequently cost as much as 100 per cent, even when imposed only upon what are commercially known as finished goods; when imposed upon materials also, the cost of collection might well run far above 200 percent in addition to the first cost of maintaining the machinery of taxation.

It must not be supposed, however, that the recovery of indirect taxes from the ultimate consumers of taxed goods is arbitrary. When shoe manufacturers, or tanners, or merchants add taxes to prices, or bankers add them to interest, it is not because they might do otherwise but choose to do this; it is because the exigencies of trade compel them. Manufacturers, merchants, and other tradesmen who carry on competitive businesses must on the average sell their goods at cost plus the ordinary rate of profit, or go out of business. It follows that any increase in cost of production tends to increase the price of products. Now, a tax upon the output of business men, which they must pay as a condition of doing their business, is as truly part of the cost of their output as is the price of the materials they buy or the wages of the men they hire. Therefore, such a tax upon business men tends to increase the price of their products. And this tendency is more or less marked as the tax is more or less great and competition more or less keen.

It is true that a moderate tax upon monopolized products, such as trade-mark goods, proprietary medicines, patented articles and copyright publications is not necessarily shifted to consumers. The monopoly manufacturer whose prices are not checked by cost of production, and are therefore as a rule higher than competitive prices would be, may find it more profitable to bear the burden of a tax that leaves him some profit, by preserving his entire custom, than to drive off part of his custom by adding the tax to his usual prices. This is true also of a moderate import tax to the extent it falls upon goods that are more cheaply transported from the place of production to a foreign market where the import tax is imposed than to a home market where the goods would be free of such a tax — products, for instance, of a farm in Canada near to a New York town, but far away from any Canadian town. If the tax be less than the difference in the cost of transportation the producer will bear the burden of it; otherwise he will not. The ultimate effect would be a reduction in the value of the Canadian land. Examples which may be cited in opposition to the principle that import taxes are indirect, will upon examination prove to be of the character here described. Business cannot be carried on at a loss — not for long.

9. "To collect taxes, to prevent and punish evasions, to check and countercheck revenue drawn from so many distinct sources, now make up probably three-fourths, perhaps seven-eighths, of the business of government outside of the preservation of order, the maintenance of the military arm, and the administration of justice." — Progress and Poverty, book iv, ch: v

10. For a brief and thorough exposition of indirect taxation read George's "Protection or Free Trade," ch. viii, on " Tariffs for Revenue."

Whoever calmly reflects and candidly decides upon the merits of indirect taxation must reject it in all its forms. But to do that is to make a great stride toward accepting the single tax. For the single tax is a form of direct taxation; it cannot be shifted.11

11. This is usually a stumbling block to those who, without much experience in economic thought, consider the single tax for the first time. As soon as they grasp the idea that taxes upon commodities shift to consumers they jump to the conclusion that similarly taxes upon land values would shift to the users. But this is a mistake, and the explanation is simple. Taxes upon what men produce make production more difficult and so tend toward scarcity in the supply, which stimulates prices; but taxes upon land, provided the taxes be levied in proportion to value, tend toward plenty in supply (meaning market supply of course), because they make it more difficult to hold valuable land idle, and so depress prices.

"A tax on rent falls wholly on the landlord. There are no means by which he can shift the burden upon anyone else. . . A tax on rent, therefore, has no effect other than its obvious one. It merely takes so much from the landlord and transfers it to the state." — John Stuart Mill's Prin. of Pol. Ec., book v, ch. iii, sec. 1.

"A tax laid upon rent is borne solely by the owner of land." — Bascom's Tr., p.159.

"Taxes which are levied on land . . . really fall on the owner of the land." — Mrs. Fawcett's Pol. Ec. for Beginners, pp.209, 210.

"A land tax levied in proportion to the rent of land, and varying with every variation of rents, . . . will fall wholly on the landlords." — Walker's Pol. Ec., ed. of 1887, p. 413, quoting Ricardo.

"The power of transferring a tax from the person who actually pays it to some other person varies with the object taxed. A tax on rents cannot be transferred. A tax on commodities is always transferred to the consumer." — Thorold Rogers's Pol. Ec., ch. xxi, 2d ed., p. 285.

"Though the landlord is in all cases the real contributor, the tax is commonly advanced by the tenant, to whom the landlord is obliged to allow it in payment of the rent." — Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations, book v, ch. ii, part ii, art. i.

"The way taxes raise prices is by increasing the cost of production and checking supply. But land is not a thing of human production, and taxes upon rent cannot check supply. Therefore, though a tax upon rent compels land-owners to pay more, it gives them no power to obtain more for the use of their land, as it in no way tends to reduce the supply of land. On the contrary, by compelling those who hold land on speculation to sell or let for what they can get, a tax on land values tends to increase the competition between owners, and thus to reduce the price of land." — Progress and Poverty, book viii, ch. iii, subd. i.

Sometimes this point is raised as a question of shifting the tax in higher rent to the tenant, and at others as a question of shifting it to the consumers of goods in higher prices. The principle is the same. Merchants cannot charge higher prices for goods than their competitors do, merely because they pay higher ground rents. A country storekeeper whose business lot is worth but few dollars charges as much for sugar, probably more, than a city grocer whose lot is worth thousands. Quality for quality and quantity for quantity, goods sell for about the same price everywhere. Differences in price are altogether in favor of places where land has a high value. This is due to the fact that the cost of getting goods to places of low land value, distant villages for example, is greater than to centers, which are places of high land value. Sometimes it is true that prices for some things are higher where land values are high. Tiffany's goods, for instance, may be more expensive than goods of the same quality at a store on a less expensive site. But that is not due to the higher land value; it is because the dealer has a reputation for technical knowledge and honesty (or has become a fad among rich people), for which his customers are willing to pay whether his store is on a high priced-lot or a low-priced one.

Though land value has no effect upon the price of good, it is easier to sell goods in some locations than in others. Therefore, though the price and the profit of each sale be the same, or even less, in good locations than in poorer ones, aggregate receipts and aggregate profits are much greater at the good location. And it is out of his aggregate, and not out of each profit, that rent is paid, For example: A cigar store on a thoroughfare supplies a certain quality of cigar for fifteen cents. On a side street the same quality of cigar can be bought no cheaper. Indeed, the cigars there are likely to be poorer, and therefore really dearer. Yet ground rent on the thoroughfare is very high compared with ground rent on the sidestreet. How, then, can the first dealer, he who pays the high ground rent, afford to sell as good or better cigars for fifteen cents than his competitor of the low priced location? Simply because he is able to make so many more sales with a given outlay of labor and capital in a given time that his aggregate profit is greater. This is due to the advantage of his location, and for that advantage he pays a premium in higher ground rent. But that premium is not charged to smokers; the competing dealer of the side street protects them. It represents the greater ease, the lower cost, of doing a given volume of business upon the site for which it is paid; add if the state should take any of it, even the whole of it, in taxation, the loss would be finally borne by the owner of the advantage which attaches to that site — by the landlord. Any attempt to shift it to tenant or buyer would be promptly checked by the competition of neighboring but cheaper land.

"A land-tax, levied in proportion to the rent of land, and varying with every variation of rent, is in effect a tax on rent; and as such a tax will not apply to that land which yields no rent, nor to the produce of that capital which is employed on the land with a view to profit merely, and which never pays rent; it will not in any way affect the price of raw produce, but will fall wholly on the landlords." — McCulloch's Ricardo (3d ed.), p. 207

2. THE TWO KINDS OF DIRECT

TAXATION

Direct taxes fall into two general classes: (1) Taxes that

are levied upon men in proportion to their ability to

pay, and (2) taxes that are levied in proportion to

the benefits received by the tax-payer from the

public. Income taxes are the principal ones of the first

class, though probate and inheritance taxes would rank

high. The single tax is the only important one of the

second class.

There should be no difficulty in choosing between the two. To tax in proportion to ability to pay, regardless of benefits received, is in accord with no principle of just government; it is a device of piracy. The single tax, therefore, as the only important tax in proportion to benefits, is the ideal tax.

But here we encounter two plausible objections. One arises from the mistaken but common notion that men are not taxed in proportion to benefits unless they pay taxes upon every kind of property they own that comes under the protection of government; the other is founded in the assumption that it is impossible to measure the value of the public benefits that each individual enjoys. Though the first of these objections ostensibly accepts the doctrine of taxation according to benefits,12 yet, as it leads to attempts at taxation in proportion to wealth, it, like the other, is really a plea for the piratical doctrine of taxation according to ability to pay. The two objections stand or fall together.

12. It is often said, for instance, by its advocates, that house owners should in justice contribute to the support of the fire departments that protect them and it is even gravely argued that houses are more appropriate subjects of taxation than land; because they need protection, whereas land needs none. Read note 8.

Let it once be perceived that the value of the service which government renders to each individual would be justly measured by the single tax, and neither objection would any longer have weight. We should then no more think of taxing people in proportion to their wealth or ability to pay, regardless of the benefits they receive from government than an honest merchant would think of charging his customers in proportion to their wealth or ability to pay, regardless of the value of the goods they bought of him." 13

13. Following is an interesting computation of the cost and loss to the city of Boston of the present mixed system of taxation as compared with the single tax; The computation was made by James R. Carret, Esq., the leading conveyancer of Boston:

Valuation of Boston, May 1, 1892

Land... ... . .. ... .. ... .. $399,170,175

Buildings ... ... ... ... ..$281,109,700

Total assessed value of real estate $680,279,875

Assessed value of personal estate $213,695,829

.... .... ... ... ... ... ... ... .... .... .... ... .... ... $893,975,704

Rate of taxation, $12.90 per $1000

Total tax levy, May 1, 1892 $11,805,036Amount of taxes levied in respect of the different subjects of taxation and percentages of the same:

Land .... .... .... .... $5,149,295 43.62%

Buildings .... .... .. $3,626,295 30.72%

Personal estate .. $2,756,676 23.35%

Polls ... .... ... .... .... ...272,750 2.31%But to ascertain the total cost to the people of Boston of the present system of taxation for the taxable year, beginning May 1, 1892, there should be added to the taxes assessed upon them what it cost them to pay the owners of the land of Boston for the use of the land, being the net ground rent, which I estimate at four per cent on the land value.

Total tax levy, May 1, 1892 ... ... ... ... .... .... .... .... .... ..... .... .... .... .... .... .... ..$11,805,036

Net ground rent, four percent, on the land value ($399,170,175)..... ... ... ...$15,966,807

Total cost of the present system to the people of Boston for that year ... $27,771,843To contrast this with what the single tax system would have cost the people of Boston for that year, take the gross ground rent, found by adding to the net ground rent the taxation on land values for that year, being $12.90 per $1000, or 1.29 per cent added to 4 per cent = 5.29 per cent.

Total cost of present system as above .. .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... ....$27,771,843

Single tax, or gross ground rent, 5.29 per cent on $399,170,175 ... ..$21,116,102

Excess cost of present system, which is the sum of

taxes in respect of buildings, personal property, and polls .... ...... .. $6,655,741But the present system not only costs the people more than the single tax would, but produces less revenue:

Proceeds of single tax ... ... ... ... ..... .... .... ..... .... .... .... ..... ..... .... $21,116,102

Present tax levy ... ... ... ... ... .... .... .... ..... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... ....$11,805,036

Loss to public treasury by present system ... .... .... .... .... .. ..... ..$9,311,066This, however, is not a complete contrast between the present system and the single tax, for large amounts of real estate are exempt from taxation, being held by the United States, the Commonwealth, by the city itself, by religious societies and corporations, and by charitable, literary, and scientific institutions. The total amount of the value of land so held as returned by the assessors for the year 1892 is $60,626,171.

Reasons can be given why all lands within the city should be assessed for taxation to secure a just distribution of the public burdens, which I cannot take the space to enter into here. There is good reason to believe also that lands in the city of Boston are assessed to quite an appreciable extent below their fair market value. As an indication of this see an editorial in the Boston Daily Advertiser for October 3, 1893, under the title, "Their Own Figures."

The vacant lands, marsh lands, and flats in Boston were valued by the assessors in 1892 (page 3 of their annual report) at $52,712,600. I believe that this represents not more than fifty per cent of their true market value.

Taking this and the undervaluation of improved property and the exemptions above mentioned into consideration, I think $500,000,000 to be a fair estimate of the land values of Boston. Making this the basis of contrast, we have:

Proceeds of single tax 5.29 per cent on $500,000,000 ... .... .... .... $26,450,000

Present tax levy ... .... ... .... .... .... .... .... ..... .... .... .... .... ..... .... .... ..$11,805,036

Loss to public treasury by present system ... ... ... ... .... .... .... ....$14,644,974

3. THE SINGLE TAX FALLS IN PROPORTION TO

BENEFITS

To perceive that the single tax would justly measure the

value of government service we have only to realize that

the mass of individuals everywhere and now, in paying for

the land they use, actually pay for government service in

proportion to what they receive. He who would enjoy the

benefits of a government must use land within its

jurisdiction. He cannot carry land from where government is

poor to where it is good; neither can he carry it from

where the benefits of good government are few or enjoyed

with difficulty to where they are many and fully enjoyed.

He must rent or buy land where the benefits of government

are available, or forego them. And unless he buys or rents

where they are greatest and most available he must forego

them in degree. Consequently, if he would work or live

where the benefits of government are available, and does

not already own land there, he will be compelled to rent or

buy at a valuation which, other things being equal, will

depend upon the value of the government service that the

site he selects enables him to enjoy. 14 Thus does he pay

for the service of government in proportion to its value to

him. But he does not pay the public which provides the

service; he is required to pay land-owners.

14. Land values are lower in all countries of poor government than in any country of better government, other things being equal. They are lower in cities of poor government, other things being equal, than in cities of better government. Land values are lower, for example, in Juarez, on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande, where government is bad, than in El Paso, the neighboring city on the American side, where government is better. They are lower in the same city under bad government than under improved government. When Seth Low, after a reform campaign, was elected mayor of Brooklyn, N.Y., rents advanced before he took the oath of office, upon the bare expectation that he would eradicate municipal abuses. Let the city authorities anywhere pave a street, put water through it and sewer it, or do any of these things, and lots in the neighborhood rise in value. Everywhere that the "good roads" agitation of wheel men has borne fruit in better highways, the value of adjacent land has increased. Instances of this effect as results of public improvements might be collected in abundance. Every man must be able to recall some within his own experience.

And it is perfectly reasonable that it should be so. Land and not other property must rise in value with desired improvements in government, because, while any tendency on the part of other kinds of property to rise in value is checked by greater production, land can not be reproduced.

Imagine an utterly lawless place, where life and property are constantly threatened by desperadoes. He must be either a very bold man or a very avaricious one who will build a store in such a community and stock it with goods; but suppose such a man should appear. His store costs him more than the same building would cost in a civilized community; mechanics are not plentiful in such a place, and materials are hard to get. The building is finally erected, however, and stocked. And now what about this merchant's prices for goods? Competition is weak, because there are few men who will take the chances he has taken, and he charges all that his customers will pay. A hundred per cent, five hundred per cent, perhaps one or two thousand per cent profit rewards him for his pains and risk. His goods are dear, enormously dear — dear enough to satisfy the most contemptuous enemy of cheapness; and if any one should wish to buy his store that would be dear too, for the difficulties in the way of building continue. But land is cheap! This is the type of community in which may be found that land, so often mentioned and so seldom seen, which "the owners actually can't give away, you know!"

But suppose that government improves. An efficient administration of justice rids the place of desperadoes, and life and property are safe. What about prices then? It would no longer require a bold or desperately avaricious man to engage in selling goods in that community, and competition would set in. High profits would soon come down. Goods would be cheap — as cheap as anywhere in the world, the cost of transportation considered. Builders and building materials could be had without difficulty, and stores would be cheap, too. But land would be dear! Improvement in government increases the value of that, and of that alone.

Now, the economic principle pursuant to which land-owners are thus able to charge their fellow-citizens for the common benefits of their common government points to the true method of taxation. With the exception of such other monopoly property as is analogous to land titles, and which in the purview of the single tax is included with land for purposes of taxation, 15 land is the only kind of property that is increased in value by government; and the increase of value is in proportion, other influences aside, to the public service which its possession secures to the occupant. Therefore, by taxing land in proportion to its value, and exempting all other property, kindred monopolies excepted — that is to say, by adopting the single tax — we should be levying taxes according to benefits.16

15. Railroad franchises, for example, are not usually thought of as land titles, but that is what they are. By an act of sovereign authority they confer rights of control for transportation purposes over narrow strips of land between terminals and along trading points. The value of this right of way is a land value.

16. Each occupant would pay to his landlord the value of the public benefits in the way of highways, schools, courts, police and fire protection, etc., that his site enabled him to enjoy. The landlord would pay a tax proportioned to the pecuniary benefits conferred upon him by the public in raising and maintaining the value of his holding. And if occupant and owner were the same, he would pay directly according to the value of his land for all the public benefits he enjoyed, both intangible and pecuniary.

And in no sense would this be class taxation. Indeed, the cry of class taxation is a rather impudent one for owners of valuable land to raise against the single tax, when it is considered that under existing systems of taxation they are exempt. 17 Even the poorest and the most degraded classes in the community, besides paying land-owners for such public benefits as come their way, are compelled by indirect taxation to contribute to the support of government. But landowners as a class go free. They enjoy the protection of the courts, and of police and fire departments, and they have the use of schools and the benefit of highways and other public improvements, all in common with the most favored, and upon the same specific terms; yet, though they go through the form of paying taxes, and if their holdings are of considerable value pose as "the tax-payers" on all important occasions, they, in effect and considered as a class, pay no taxes, because government, by increasing the value of their land, enables them to recover back in higher rents and higher prices more than their taxes amount to. Enjoying the same tangible benefits of government that others do, many of them as individuals and all of them as a class receive in addition a tangible pecuniary benefit which government confers upon no other property-owners. The value of their property is enhanced in proportion to the benefits of government which its occupants enjoy. To tax them alone, therefore, is not to discriminate against them; it is to charge them for what they get.18

17. While the landholders of the City of Washington were paying something less than two per cent annually in taxes, a Congressional Committee (Report of the Select Committee to Investigate Tax Assessments in the District of Columbia, composed of Messrs. Johnson, of Ohio, Chairman, Wadsworth, of New York, and Washington, of Tennessee. Made to the House of Representatives, May 24, 1892. Report No. 1469), brought out the fact that the value of their land had been increasing at a minimum rate of ten per cent per annum. The Washington land-owners as a class thus appear to have received back in higher land values, actually and potentially, about ten dollars for every two dollars that as land-owners they paid in taxes. If any one supposes that this condition is peculiar to Washington let him make similar estimates for any progressive locality, and see if the land-owners there are not favored in like manner.

But the point is not dependent upon increase in the capitalized value of land. If the land yields or will yield to its owner an income in the nature of actual or potential ground rent, then to the extent that this actual or possible income is dependent upon government the landlord is in effect exempt from taxation. No matter what tax he pays on account of his ownership of land, the public gives it back to him to that extent.

18. Take for illustration two towns, one of excellent government and the other of inefficient government, but in all other respects alike. Suppose you are hunting for a place of residence and find a suitable site in the town of good government. For simplicity of illustration let us suppose that the land there is not sold outright but is let upon ground rent. You meet the owner of the lot you have selected and ask him his terms. He replies:

"Two hundred and fifty dollars a year."

"Two hundred and fifty dollars a year!" you exclaim. "Why, I can get just as good a site in that other town for a hundred dollars a year."

"Certainly you can," he will say. "But if you build a house there and it catches fire it will burn down; they have no fire department. If you go out after dark you will be 'held up' and robbed; they have no police force. If you ride out in the spring, your carriage will stick in the mud up to the hubs, and if you walk you may break your legs and will be lucky if you don t break your neck; they have no street pavements and their sidewalks are dangerously out of repair. When the moon doesn't shine the streets are in darkness, for they have no street lights. The water you need for your house you must get from a well; there is no water supply there. Now in our town it is different. We have a splendid fire department, and the best police force in the world. Our streets are macadamized, and lighted with electricity; our sidewalks are always in first class repair; we have a water system that equals that of New York; and in every way the public benefits in this town are unsurpassed. It is the best governed town in all this region. Isn't it worth a hundred and fifty dollars a year more for a building site here than over in that poorly governed town?"

You recognize the advantages and agree to the terms. But when your house is built and the assessor visits you officially, what would be the conversation if your sense of the fitness of things were not warped by familiarity with false systems of taxation? Would it not be something like what follows?

"How much do you regard this house as worth? " asks the assessor.

"What is that to you?" you inquire.

"I am the town assessor and am about to appraise your property for taxation."

"Am I to be taxed by this town? What for?"

"What for?" echoes the assessor in surprise. "What for? Is not your house protected from fire by our magnificent fire department? Are not you protected from robbery by the best police force in the world? Do not you have the use of macadamized pavements, and good sidewalks, and electric street lights, and a first class water supply? Don't you suppose these things cost something? And don't you think you ought to pay your share?"

"Yes," you answer, with more or less calmness; "I do have the benefit of these things, and I do think that I ought to pay my share toward supporting them. But I have already paid my share for this year. I have paid it to the owner of this lot. He charges me two hundred and fifty dollars a year -- one hundred and fifty dollars more than I should pay or he could get but for those very benefits. He has collected my share of this year's expense of maintaining town improvements; you go and collect from him. If you do not, but insist upon collecting from me, I shall be paying twice for these things, once to him and once to you; and he won't be paying at all, but will be making money out of them, although he derives the same benefits from them in all other respects that I do."

4. CONFORMITY TO GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF TAXATION

The single tax conforms most closely to the essential principles of Adam Smith's four classical maxims, which are stated best by Henry George 19 as follows:

The best tax by which public revenues can be raised is evidently that which will closest conform to the following conditions:

- That it bear as lightly as possible upon production — so as least to check the increase of the general fund from which taxes must be paid and the community maintained. 20

- That it be easily and cheaply collected, and fall as directly as may be upon the ultimate payers — so as to take from the people as little as possible in addition to what it yields the government. 21

- That it be certain — so as to give the least opportunity for tyranny or corruption on the part of officials, and the least temptation to law-breaking and evasion on the part of the tax-payers. 22

- That it bear equally — so as to give no citizen an advantage or put any at a disadvantage, as compared with others. 23

19. "Progress and Poverty," book viii. ch.iii.

20. This is the second part of Adam Smith's fourth maxim. He states it as follows: "Every tax ought to be so contrived as both to take out and to keep out of the pockets of the people as little as possible over and above what it brings into the public treasury of the state. A tax may either take out or keep out of the pockets of the people a great deal more than it brings into the public treasury in the four following ways: . . . Secondly, it may obstruct the industry of the people, and discourage them from applying to certain branches of business which might give maintenance and employment to great multitudes. While it obliges the people to pay, it may thus diminish or perhaps destroy some of the funds which might enable them more easily to do so."

21. This is the first part of Adam Smith's fourth maxim, in which he condemns a tax that takes out of the pockets of the people more than it brings into the public treasury.

22. This is Adam Smith's second maxim. He states it as follows: "The tax which each individual is bound to pay ought to be certain and not arbitrary. The time of payment, the manner of payment, the quantity to be paid, ought all to be clear and plain to the contributor and to every other person. Where it is otherwise, every person subject to the tax is put more or less in the power of the tax gatherer."

23. This is Adam Smith's first maxim. He states it as follows: "The subjects of every state ought to contribute towards the support of the government as nearly as possible in proportion to their respective abilities, that is to say, in proportion to the revenue which they respectively enjoy under the protection of the state. The expense of government to the individuals of a great nation is like the expense of management to the joint tenants of a great estate, who are all obliged to contribute in proportion to their respective interests in the estate. In the observation or neglect of this maxim consists what is called the equality or inequality of taxation."

In changing this Mr. George says ("Progress and Poverty," book viii, ch. iii, subd. 4): "Adam Smith speaks of incomes as enjoyed 'under the protection of the state'; and this is the ground upon which the equal taxation of all species of property is commonly insisted upon — that it is equally protected by the state. The basis of this idea is evidently that the enjoyment of property is made possible by the state — that there is a value created and maintained by the community; which is justly called upon to meet community expenses. Now, of what values is this true? Only of the value of land. This is a value that does not arise until a community is formed, and that, unlike other values, grows with the growth of the community. It only exists as the community exists. Scatter again the largest community, and land, now so valuable, would have no value at all. With every increase of population the value of land rises; with every decrease it falls. This is true of nothing else save of things which, like the ownership of land, are in their nature monopolies."

Adam Smith's third maxim refers only to conveniency of payment, and gives countenance to indirect taxation, which is in conflict with the principle of his fourth maxim. Mr. George properly excludes it.

a. Interference with Production

Indirect taxes tend to check production and cause scarcity,

by obstructing the processes of production. They fall upon

men as they work, as they do business,

as they invest capital productively. 24 But the

single tax, which must be paid and be the same in amount

regardless of whether the payer works or plays, of whether

he invests his capital productively or wastes it, of

whether he uses his land for the most productive purposes

25 or in lesser degree or not at all, removes fiscal

penalties from industry and thrift, and tends to leave

production free. It therefore conforms more closely than

indirect taxation to the first maxim quoted above.

24. "Taxation which falls upon the processes of production interposes an artificial obstacle to the creation of wealth. Taxation which falls upon labor as it is exerted, wealth as it is used as capital, land as it is cultivated, will manifestly tend to discourage production much more powerfully than taxation to the same amount levied upon laborers whether they work or play, upon wealth whether used productively or unproductively, or upon land whether cultivated or left waste" — Progress and Poverty, book viii, ch. iii, subd. I.

25. It is common, besides taxing improvements, as fast as they are made, to levy higher taxes upon land when put to its best use than when put to partial use or to no use at all. This is upon the theory that when his land is used the owner gets full income from it and can afford to pay high taxes; but that he gets little or no income when the land is out of use, and so cannot afford to pay much. It is an absurd but perfectly legitimate illustration of the pretentious doctrine of taxation according to ability to pay.

Examples are numerous. Improved building lots, and even those that are only plotted for improvement, are usually taxed more than contiguous unused and unplotted land which is equally in demand for building purposes and equally valuable. So coal land, iron land, oil land, and sugar land are as a rule taxed less as land when opened up for appropriate use than when lying idle or put to inferior uses, though the land value be the same. Any serious proposal to put land to its appropriate use is commonly regarded as a signal for increasing the tax upon it.

b. Cheapness of Collection

Indirect taxes are passed along from first payers to final consumers through many exchanges, accumulating compound profits as they go, until they take enormous sums from the people in addition to what the government receives.26 But the single tax takes nothing from the people in excess of the tax. It therefore conforms more closely than indirect taxation to the second maxim quoted above.

26. "All taxes upon things of unfixed quantity increase prices, and in the course of exchange are shifted from seller to buyer, increasing as they go. If we impose a tax on money loaned, as has been often attempted, the lender will charge the tax to the borrower, and the borrower must pay it or not obtain the loan. If the borrower uses it in his business, he in his turn must get back the tax from his customers, or his business becomes unprofitable. If we impose a tax upon buildings, the users of buildings must finally pay it, for the erection of buildings will cease until building rents become high enough to pay the regular profit and the tax besides. If we impose a tax upon manufactures or imported goods, the manufacturer or importer will charge it in a higher price to the jobber, the jobber to the retailer. and the retailer to the consumer. Now, the consumer, on whom the tax thus ultimately falls, must not only pay the amount of the tax, but also a profit on this amount to everyone who has thus advanced it — for profit on the capital he has advanced in paying taxes is as much required by each dealer as profit on the capital he has advanced in paying for goods." — Progress and Poverty, book viii, ch. iii, subd. 2.

c. Certainty

No other tax, direct or indirect, conforms so closely to the third maxim. "Land lies out of doors." It cannot be hidden; it cannot be "accidentally" overlooked. Nor can its value be seriously misstated. Neither under-appraisement nor over-appraisement to any important degree is possible without the connivance of the whole community. 27 The land values of a neighborhood are matters of common knowledge. Any intelligent resident can justly appraise them, and every other intelligent resident can fairly test the appraisement. Therefore, the tyranny, corruption, fraud, favoritism, and evasions that are so common in connection with the taxation of imports, manufactures, incomes, personal property, and buildings — the values of which, even when the object itself cannot be hidden, are so distinctly matters of minute special knowledge that only experts can fairly appraise them — would be out of the question if the single tax were substituted for existing fiscal methods. 28

27. The under-appraisements so common at present, and alluded to in note 25, are possible because the community, ignorant of the just principles of taxation, does connive at them. Under-appraisements are not secret crimes on the part of assessors; they are distinctly recognized, but thoughtlessly disregarded when not actually insisted upon, by the people themselves. And this is due to the dishonest ideas of taxation that are taught. Let the vicious doctrine that people ought to pay taxes according to their ability give way to the honest principle that they should pay in proportion to the benefits they receive, which benefits, as we have already seen, are measured by the land values they own, and underappraisement of land would cease. No assessor can befool the community in respect of the value of the land within his jurisdiction.

And, with the cessation of general under-appraisement, favoritism in individual appraisements also would cease. General under-appraisement fosters unfair individual appraisements. If land were generally appraised at its full value, a particular unfair appraisement would stand out in such relief that the crime of the assessor would be exposed. But now if a man's land is appraised at a higher valuation than his neighbor's equally valuable land, and he complains of the unfairness, he is promptly and effectually silenced with a warning that his land is worth much more than it is appraised at, anyhow, and if he makes a fuss his appraisement will be increased. To complain further of the deficient taxation of his neighbor is to invite the imposition of a higher tax upon himself.

28. If you wish to test the merits in point of certainty of the single tax as compared with other taxes, go to a real estate agent in your community, and, showing him a building lot upon the map, ask him its value. If he inquires about the improvements, instruct him to ignore them. He will be able at once to tell you what the lot is worth. And if you go to twenty other agents their estimates will not materially vary from his. Yet none of the agents will have left his office. Each will have inferred the value from the size and location of the lot.

But suppose when you show the map to the first agent you ask him the value of the land and its improvements. He will tell you that he cannot give an estimate until he examines the improvements. And if it is the highly improved property of a rich man he will engage building experts to assist him. Should you ask him to include the value of the contents of the buildings, he would need a corps of selected experts, including artists and liverymen, dealers in furniture and bric-a-brac, librarians and jewelers. Should you propose that he also include the value of the occupant's income, the agent would throw up his hands in despair.

If without the aid of an army of experts the agent should make an estimate of these miscellaneous values, and twenty others should do the same, their several estimates would be as wide apart as ignorant guesses usually are. And the richer the owner of the property the lower as a proportion would the guesses probably be.

Now turn the real estate agent into an assessor, and is it not plain that he would appraise the land values with much greater certainty and cheapness than he could appraise the values of all kinds of property? With a plot map before him he might fairly make every appraisement without leaving his desk at the town hall.

And there would be no material difference if the property in question were a farm instead of a building lot. A competent farmer or business man in a farming community can, without leaving his own door-yard, appraise the value of the land of any farm there; whereas it would be impossible for him to value the improvements, stock, produce, etc., without at least inspecting them.

d. Equality

In respect of the fourth maxim the single tax bears more equally— that is to say, more justly — than any other tax. It is the only tax that falls upon the taxpayer in proportion to the pecuniary benefits he receives from the public; 29 and its tendency, accelerating with the increase of the tax, is to leave every one the full fruit of his own productive enterprise and effort. 30

29 The benefits of government are not the only public benefits whose value attaches exclusively to land. Communal development from whatever cause produces the same effect. But as it is under the protection of government that land-owners are able to maintain ownership of land and through that to enjoy the pecuniary benefits of advancing social conditions, government confers upon them as a class not only the pecuniary benefits of good government but also the pecuniary benefits of progress in general.

30. "Here are two men of equal incomes — that of the one derived from the exertion of his labor, that of the other from the rent of land. Is it just that they should equally contribute to the expenses of the state? Evidently not. The income of the one represents wealth he creates and adds to the general wealth of the state; the income of the other represents merely wealth that he takes from the general stock, returning nothing." — Progress and Poverty, book viii, ch. iii, subd. 4.

III. THE SINGLE TAX AS A SOCIAL REFORM.

But the single tax is more than a revenue system. Great as are its merits in this respect, they are but incidental to its character as a social reform.31 And that some social reform, which shall be simple in method but fundamental in character, is most urgently needed we have only to look about us to see.

31. There are two classes of single tax advocates. Those who advocate it as a reform in taxation alone, regardless of its effects upon social adjustments, are called "single tax men limited"; those who advocate it both as a reform in taxation and as the mode of securing equal rights to land, are called "single tax men unlimited."

Poverty is widespread and pitiable. This we know. Its general manifestations are so common that even good men look upon it as a providential provision for enabling the rich to drive camels through needles' eyes by exercising the modern virtue of organized giving.32 Its occasional manifestations in recurring periods of "hard times"33 are like epidemics of a virulent disease, which excite even the most contented to ask if they may not be the next victims. Its spasms of violence threaten society with anarchy on the one hand, and, through panic-stricken efforts at restraint, with loss of liberty on the other. And it persists and deepens despite the continuous increase of wealth producing power.34

32. Not all charity is contemptible. Those charitable people, who, knowing that individuals suffer, hasten to their relief, deserve the respect and affection they receive. That kind of charity is neighborliness; it is love. And perhaps in modern circumstances organization is necessary to make it effective. But organized charity as a cherished social institution is a different thing. It is not love, nor is it inspired by love; it is simply sanctified selfishness, at the bottom of which will be found the blasphemous notion that in the economy of God the poor are to be forever with us that the rich may gain heaven by alms-giving.

Suppose a hole in the sidewalk into which passers-by continually fall, breaking their arms, their legs, and sometimes their necks. We should respect charitable people who, without thought of themselves, went to the relief of the sufferers, binding the broken limbs of the living, and decently burying the dead. But what should we say of those who, when some one proposed to fill up the hole to prevent further suffering, should say, "Oh, you mustn't fill up that hole! Whatever in the world should we charitable people do to be saved if we had no broken legs and arms to bind, and no broken-necked people to bury?"

Of some kinds of charity it has been well said that they are "that form of self-righteousness which makes us give to others the things that already belong to them." They suggest the old nursery rhyme:

"There was once a considerate crocodile,

Which lay on a bank of the river Nile.

And he swallowed a fish, with a face of woe,

While his tears flowed fast to the stream below.

'I am mourning,' said he, 'the untimely fate

Of the dear little fish which I just now ate.'"Read Chapter viii of "Social Problems," by Henry George, entitled, "That We All Might Be Rich."

33. Differences between "hard times" and "good times" are but differences in degrees of poverty and in the people who suffer from it. Times are always hard with the multitude. But the voice of the multitude is too weak to be heard at ordinary times through the ordinary trumpets of public opinion. They are not regarded nor do they regard themselves as people of any importance in the industrial world, so long as the general wheels of business revolve. It is only when poverty has eaten its way up through the various strata of struggling and pinching and squeezing and squirming humanity, and with its cancerous tentacles touched the superincumbent layers of manufacturing nabobs, merchant princes, railroad kinds, great bankers and great landowners that we hear any general complain of "hard times."

34. "Could a man of the last century — a Franklin or a Priestley — have seen, in a vision of the future, the steamship taking the place of the sailing vessel, the railroad train of the wagon, the reaping machine of the scythe, the threshing machine of the flail; could he have heard the throb of the engines that in obedience to human will, and for the satisfaction of human desire, exert a power greater than that of all the men and all the beasts of burden of the earth combined; could he have seen the forest tree transformed into finished lumber — into doors, sashes, blinds, boxes or barrels, with hardly the touch of a human hand; the great workshops where boots and shoes are turned out by the case with less labor than the old-fashioned cobbler could have put on a sole; the factories where, under the eye of a girl, cotton becomes cloth faster than hundreds of stalwart weavers could have turned it out with their hand-looms; could he have seen steam hammers shaping mammoth shafts and mighty anchors, and delicate machinery making tiny watches; the diamond drill cutting through the heart of the rocks, and coal oil sparing the whale; could he have realized the enormous saving of labor resulting from improved facilities of exchange and communication — sheep killed in Australia eaten fresh in England and the order given by the London banker in the afternoon executed in San Francisco in the morning of the same day; could he have conceived of the hundred thousand improvements which these only suggest, what would he have inferred as to the social condition of mankind?

"It would not have seemed like an inference; further than the vision went, it would have seemed as though he saw; and his heart would have leaped and his nerves would have thrilled, as one who from a height beholds just ahead of the thirst-stricken caravan the living gleam of rustling woods and the glint of laughing waters. Plainly, in the sight of the imagination, he would have beheld these new forces elevating society from its very foundations, lifting the very poorest above the possibility of want, exempting the very lowest from anxiety for the material needs of life ... And out of these bounteous material conditions he would have seen arising, as necessary sequences, moral conditions realizing the golden age of which mankind have always dreamed. ... More or less vague or clear, these have been the hopes, these the dreams born of the improvements which give this wonderful century its preeminence. ... It is true that disappointment has followed disappointment, and that discovery upon discovery, and invention after invention, have neither lessened the toil of those who most need respite, nor brought plenty to the poor. But there have been so many things to which it seemed this failure could be laid, that up to our time the new faith has hardly weakened. ... Now, however, we are coming into collision with facts which there can be no mistaking. ... And, unpleasant as it may be to admit it, it is at last becoming evident that the enormous increase in productive power which has marked the present century and is still going on with accelerating ratio, has no tendency to extirpate poverty or to lighten the burdens of those compelled to toil. It simply widens the gulf between Dives and Lazarus, and makes the struggle for existence more intense. The march of invention has clothed mankind with powers of which a century ago the boldest imagination could not have dreamed. But in factories where labor-saving machinery has reached its most wonderful development, little children are at work; wherever the new forces are anything like fully utilized, large classes are maintained by charity or live on the verge of recourse to it; amid the greatest accumulations of wealth, men die of starvation, and puny infant suckle dry breasts; while everywhere the greed of gain, the worship of wealth, shows the force of the fear of want. — Progress and Poverty, Introduction.

That much of our poverty is involuntary may be proved, if proof be necessary, by the magnitude of charitable work that aims to help only the "deserving poor"; and as to undeserving cases — the cases of voluntary poverty — who can say but that they, if not due to birth and training in the environs of degraded poverty, 35 are the despairing culminations of long-continued struggles for respectable independence? 36 How can we know that they are not essentially like the rest — involuntary and deserving? It is a profound distinction that a clever writer of fiction 37 makes when he speaks of "the hopeful and the hopeless poor." There is, indeed, little difference between voluntary and involuntary poverty, between the "deserving" and the "undeserving" poor, except that the "deserving" still have hope, while from the "undeserving" all hope, if they ever knew any, has gone.

35. The leader of one of the labor strikes of the early eighties, a hard-working, respectable, and self-respecting man, told me that the deprivations which he himself suffered as a workingman were as nothing compared with the fear for the future of his children that he felt whenever he thought of the repulsive surroundings, physical and moral, in which, owing to his poverty, he was compelled to bring them up.

Professor Francis Wayland, Dean of the Yale law school, wrote in the Charities Review for March, 1893: "Under our eyes and within our reach, children are being reared from infancy amid surroundings containing every conceivable element of degradation, depravity and vice. Why, then, should we be surprised that we are surrounded by a horde of juvenile delinquents, that the police reports in our cities teem with the exploits of precocious little villains, that reform schools are crowded with hopelessly abandoned young offenders? How could it be otherwise? What else could be expected from such antecedents, from such ever-present examples of flagrant vice? Short of a miracle, how could any child escape the moral contagion of such an environment? How could he retain a single vestige of virtue, a single honest impulse, a single shred of respect for the rights of others, after passing through such an ordeal of iniquity? What is there left on which to build up a better character?

In the Arena of July, 1893, Helen Campbell says, "It would seem at times as if the workshop meant only a form of preparation for the hospital, the workhouse and the prison, since the workers therein become inoculated with trade diseases, mutilated by trade appliances, and corrupted by trade associates till no healthy fiber, mental, moral or physical, remains."

Such testimony is abundant. But no further citation is necessary to arouse the conscience of the merciful and the just, and any amount of proof would not affect those self-satisfied mortals whom Kipling describes when he says that "there are men who, when their own front doors are closed, will swear that the whole world's warm."

36. Some years ago a gentleman, now well and favorably known in New York public life, told me of a ragged tramp whom he had brought, more to gratify a whim perhaps than in any spirit of philanthropy, from a neighboring camp of tramps to his house for breakfast. After breakfast the host asked his guest, in the course of conversation, why he lived the life of a tramp. This in substance was the tramp's reply:

"I am a mechanic and used to be a good one, though not so exceptionally good as to be safe from the competition of the great class of average workers. I had a family — a wife and two children. In the hard times of the seventies I lost my job. For a while we lived upon our little savings; but sickness came and our savings were used up. My wife and children died. Everything was gone but self-respect. Then I traveled, looking for work which could not be had at home. I traveled afoot; I could afford no other way. For days I hunted for work, begging food and sleeping in barns or under trees; but no work could I get. Once or twice I was arrested as a vagrant. Then I fell in with a party of tramps and with them drifted into the city. Winter came on. I still had a desire to regain my old place as a self-respecting man, but work was scarce and nothing that I could do could I find to do, except some little job now and then which was given to me as pennies are given to beggars. I slept mostly in station houses. Part of the time I was undergoing sentence for vagrancy. In the spring I tramped again. But now I did not hunt for work. My self-respect was gone so completely that I had no ambition to regain it. I was a loafer and a jail-bird. I had no family to support, and I had found that, barring the question of self-respect, I was about as well off as were average workmen. After years of tramping this opinion is unchanged. I am always sure of enough to eat and a place to sleep in — not very good often, but good enough. I should not be sure of that if I were a workingman. I might lose my job and go hungry rather than beg. I might be unable to pay my rent and so be turned upon the street. I might marry again and have a family which would be condemned to the hard life of the average workingman's family. And as for society, why, I have society. Tramps are good fellows — sociable fellows, bright fellows many of them. Life as a tramp is not half bad when you compare it with the workingman's life, leaving out the question of self-respect, of course. You must leave that out. No man can be a tramp for good until he loses that. But a period of hard times makes many a chap lose it. And as I have lost it I would rather be a tramp than a workingman. I have tried both. By the way, Mr. ——, this is a very good cigar — this brand of yours. I seldom smoke much better cigars."

The facts in detail of this man's story may have been false; they probably were. But so were the facts in detail of Bunyan's "Pilgrim's Progress." There is, however, a distinction between fact and truth, and no matter how false the man's facts may have been, his story, like Bunyan's, was essentially true. Much of the poverty that upon the surface seems to be voluntary and undeserving comes from a growing feeling among those who work hardest that, as Cowper describes it, they are

"Letting down buckets into empty wells,

And growing old with drawing nothing up."At Victoria, B.C., in the spring of 1894, I witnessed a canoe race in which there were two contestants and but one prize. Long before the winner had reached the goal his adversary, who found himself far behind, turned his canoe toward the shore and dropped out of the race. Was it because he was too lazy to paddle? Not at all. It was because he realized the hopelessness of the effort.

37. H. C. Bunner, editor of Puck.

But it is not alone to objects of charity that the question of poverty calls our attention. There is a keener poverty, which pinches and goes hungry, but is beyond the reach of charity because it never complains. And back of all and over all is fear of poverty, which chills the best instincts of men of every social grade, from recipients of out-door relief who dread the poorhouse, to millionaires who dread the possibility of poverty for their children if not for themselves.38

38. A well known millionaire is quoted as saying: "I would rather leave my children penniless in a world in which they could at all times obtain employment for wages equal to the value of their work as measured by the work of others, than to leave them millions of dollars in a world like this, where if thy lose their inheritance, they may have no chance of earning am decent living."

It is poverty and fear of poverty that prompt men of honest instincts to steal, to bribe, to take bribes, to oppress, either under color of law or against law, and — what is worst than all, because it is not merely a depraved act, but a course of conduct that implies a state of depravity — to enlist their talents in crusades against their convictions. 39 Our civilization cannot long resist such enemies as poverty and fear of poverty breed; to intelligent observers it already seems to yield. 40

39. "From whence springs this lust for gain, to gratify which men tread everything pure and noble under their feet; to which they sacrifice all the higher possibilities of life; which converts civility into a hollow pretense, patriotism into a sham, and religion into hypocrisy; which makes so much of civilized existence an Ishmaelitish warfare, of which the weapons are cunning and fraud? Does it not spring from the existence of want? Carlyle somewhere says that poverty is the hell of which the modern Englishman is most afraid. And he is right. Poverty is the openmouthed, relentless hell which yawns beneath civilized society. And it is hell enough. The Vedas declare no truer thing than when the wise crow Bushanda tells the eagle-bearer of Vishnu that the keenest pain is in poverty. For poverty is not merely deprivation; it means shame, degradation; the searing of the most sensitive parts of our moral and mental nature as with hot irons; the denial of the strongest impulses and the sweetest affections; the wrenching of the most vital nerves. You love your wife, you love your children; but would it not be easier to see them die than to see them reduced to the pinch of want in which large classes in every highly civilized community live? ... From this hell of poverty, it is but natural that men should make every effort to escape. With the impulse to self-preservation and self-gratification combine nobler feelings, and love as well as fear urges in the struggle. Many a man does a mean thing, a dishonest thing, a greedy and grasping and unjust thing, in the effort to place above want, or the fear of want, mother or wife or children." — Progress and Poverty, book ix, ch iv.

40. "There is just now a disposition to scoff at any implication that we are not in all respects progressing ... Yet it is evident that there have been times of decline, just as there have been times of advance; and it is further evident that these epochs of decline could not at first have been generally recognized.

"He would have been a rash man who, when Augustus was changing the Rome of brick to the Rome of marble, when wealth was augmenting and magnificence increasing, when victorious legions were extending the frontier, when manners were becoming more refined, language more polished, and literature rising to higher splendors — he would have been a rash man who then would have said that Rome was entering her decline. Yet such was the case.

"And whoever will look may see that though our civilization is apparently advancing with greater rapidity than ever, the same cause which turned Roman progress into retrogression is operating now.

"What has destroyed every previous civilization has been the tendency to the unequal distribution of wealth and power. This same tendency, operating with increasing force, is observable in our civilization today, showing itself in every progressive community, and with greater intensity the more progressive the community. ... The conditions of social progress, as we have traced the law, are association and equality. The general tendency of modern development, since the time when we can first discern the gleams of civilization in the darkness which followed the fall of the Western Empire, has been toward political and legal equality ... This tendency has reached its full expression in the American Republic, where political and legal rights are absolutely equal ... it is the prevailing tendency, and how soon Europe will be completely republican is only a matter of time, or rather of accident. The United States are therefore in this respect, the most advanced of all the great nations, in a direction in which all are advancing, and in the United States we see just how much this tendency to personal and political freedom can of itself accomplish. ... It is now ... evident that political equality, coexisting with an increasing tendency to the unequal distribution of wealth, must ultimately beget either the despotism of organized tyranny or the worse despotism of anarchy.

"To turn a republican government into a despotism the basest and most brutal, it is not necessary formally to change its constitution or abandon popular elections. It was centuries after Cæsar before the absolute master of the Roman world pretended to rule other than by authority of a Senate that trembled before him.